This section aims to present the results and discuss the findings of the study in relation

to the research question and objectives. The primary objective of the research is to assess the

effectiveness of using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data for flood monitoring and mapping. The

research question focuses on the accuracy and reliability of these remote sensing techniques in

identifying flood inundation areas. Through the application of water indices, namely NDWI and

WRI, the study seeks to extract floodwater areas and generate flood inundation maps[14]. The

NDWI index utilizes the spectral characteristics of water and vegetation in the Near-Infrared

(NIR) and green bands, while the WRI index combines the green, red, and NIR bands to

estimate the extent of floodwater. These indices provide valuable information for detecting and

mapping flood events.

Indices Calculation:

Image Selection Based on Cloud Cover:

The selection of images with low cloud cover was driven by the need to obtain highquality and cloud-free imagery for accurate flood extent estimation. Cloud cover can significantly

hinder the visibility of the Earth's surface, particularly in optical satellite imagery such as

Sentinel-2 data, which relies on visible and near-infrared bands for water detection. By choosing

images with minimal cloud cover, the research aimed to minimize the potential for

misclassification or ambiguity in identifying flooded areas.

This selection strategy was based on historical cloud cover patterns and climatic

conditions specific to the study area. By selecting days with reduced cloud cover, the probability

of obtaining clear, high-quality images that accurately depict the magnitude of the floodwater

was heightened. The emphasis on obtaining images with minimal cloud cover aligns with the

objective of achieving accurate and reliable flood extent mapping. Clear imagery allows for better

discrimination between water and non-water areas, reducing uncertainties in the analysis. By

minimizing the impact of cloud cover, the research aimed to enhance the precision and quality

of the derived flood extent maps, thereby enabling more robust flood monitoring and

management [15]. It is worth noting that while selecting images with low cloud cover increases

the likelihood of capturing clear flood extent information, it is still important to consider the

limitations and potential influence of residual clouds or cloud shadows in the imagery. These

factors will be taken into account during the analysis and interpretation of the obtained flood

inundation maps.

The Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI):

NDWI for July-2022:

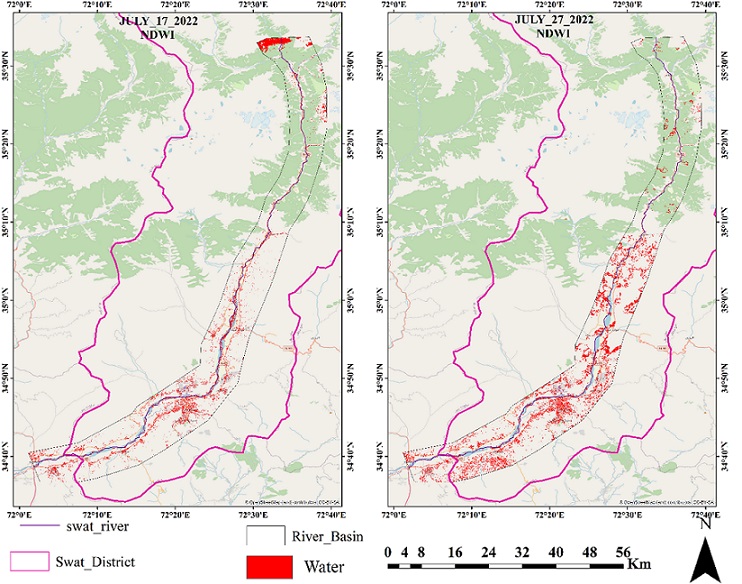

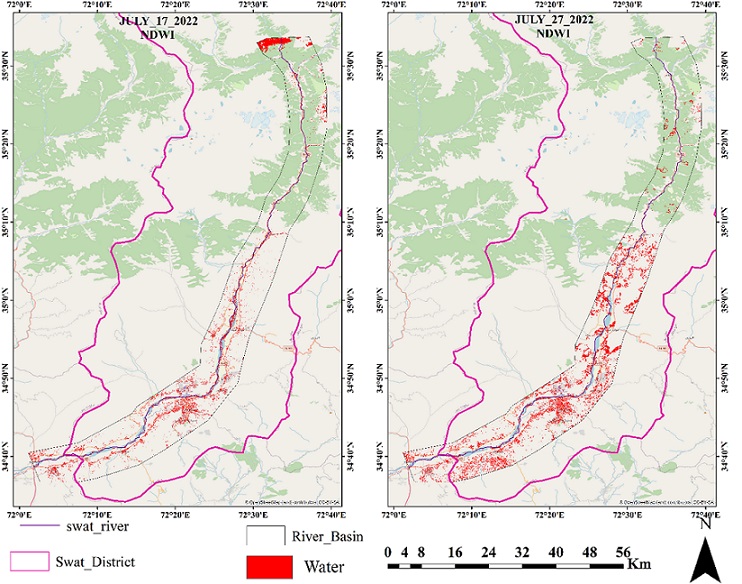

The flood inundation maps based on the NDWI for the images captured on 17th July

and 27th July revealed important insights into the extent and intensity of the flooding in the

study area. Here is a summary of the findings based on the two images:

Image of 17th July:

• The image shows a total flooded area of approximately 2,634 hectares.

• Among the selected areas, the most affected regions are Charbagh, Manglor, Mangora,

Saidu Sharif, and Chakdara.

• These areas experienced significant flooding, indicating a substantial presence of water

bodies and potential damage to infrastructure and communities.

Image of 27th July:

• The image indicates a higher intensity of floodwater compared to the image from 17th

July.

• The total flooded area has increased to approximately 7565 hectares.

• With the exception of Kalam, all other nine areas experienced flooding.

• The areas most affected by the flood include Mangora and Saidu Sharif, followed by

Charbagh and Khwazakhela.

These findings suggest a progressive intensification of the flood event between the two

dates, with a larger area being affected by floodwaters on 27th July. The identified areas of

Charbagh, Mangora, Saidu Sharif, and Chakdara consistently showed high vulnerability to

flooding, indicating the need for focused flood management and mitigation measures in these

regions. The analysis of these images provided valuable information on the spatial distribution

of floodwaters, allowing for a better understanding of the extent and severity of the flooding in

the study area. Figure 1 shows spatial temporal flood area for the month of July using NDWI.

This knowledge can support decision-making processes related to emergency response, resource

allocation, and long-term flood mitigation strategies [16].

Figure 1: Spatial -temporal flood area extent for July month using the NDWI

NDWI for August-2022:

The analysis of Sentinel-2 satellite imagery for August 2022 provides valuable insights

into the extent of floodwater in the study area. Three images were obtained on different days:

5th August, 13th August, and 28th August. These specific days were selected to ensure the

acquisition of images with the lowest possible cloud cover, enhancing the quality and accuracy

of the results. The selection of specific days for imagery acquisition was based on the aim of

obtaining images with low cloud cover. Cloud cover can obstruct the visibility of floodwater and

affect the accuracy of the results. By selecting days with minimal cloud cover, the study aimed

to ensure clearer and more reliable floodwater mapping. This approach enhances the confidence

in the obtained results and facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of the spatial

distribution of flood extent in the study area [17]. On the 5th of August, the image revealed a

water extent of approximately 8,629 hectares, which accounts for about 8% of the overall basin

area. The most affected areas in this image were Mangora and Saidu Sharif, indicating localized

flooding in these regions.

Figure 2: Spatial -temporal flood area extent for August month using the NDWI

Moving to the 13th of August, the floodwater extent increased significantly. The image

showed an expanded water coverage of around 9,573 hectares, representing about 9% of the

total basin area. Mangora and Saidu Sharif remained highly affected, and the flood extent

expanded to other areas such as Charbagh, Manglor, Barikot, and Chakdara. The final image

acquired on the 28th of August depicted the highest water content among the three images. The

floodwater extent reached approximately 22,553 hectares, which accounts for about 21% of the

total basin area. The most heavily affected areas shifted to Kalam and Bahrain, with substantial

flooding observed in these regions. Additionally, all other districts in the study area exhibited a

high vulnerability to flood extent, except for Chakdara. These findings underscore the

progressive increase in the extent and intensity of the floodwater as the month of August

advanced. Mangora, Saidu Sharif, and Chakdara consistently experienced significant floodwater

presence, highlighting their high vulnerability to floods [18]. Moreover, the districts of Charbagh,

Manglor, Barikot, Kalam, and Bahrain were also significantly affected in various images,

indicating the need for targeted flood mitigation measures in these areas. Overall, the analysis of

Sentinel-2 imagery for August 2022 provides critical insights into the temporal variation and

spatial distribution of floodwater extent, enabling informed decision-making processes for

emergency response planning, resource allocation, and the implementation of effective flood

mitigation strategies in the study area.

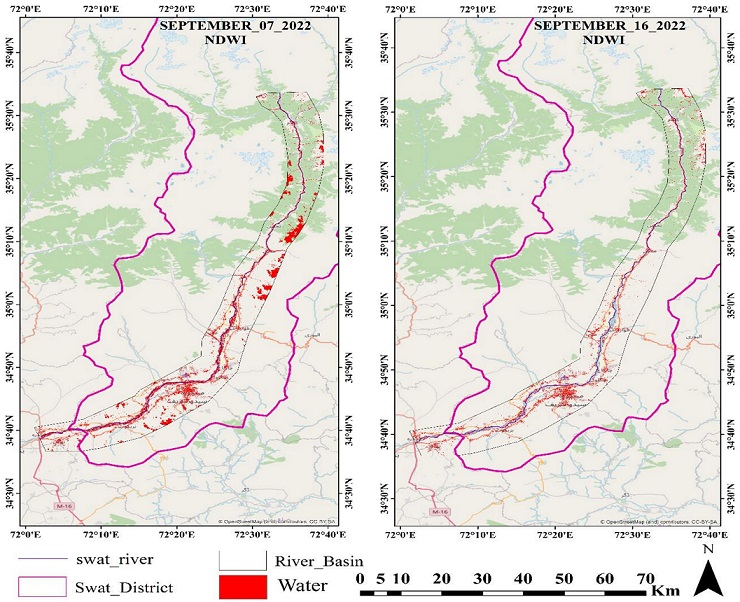

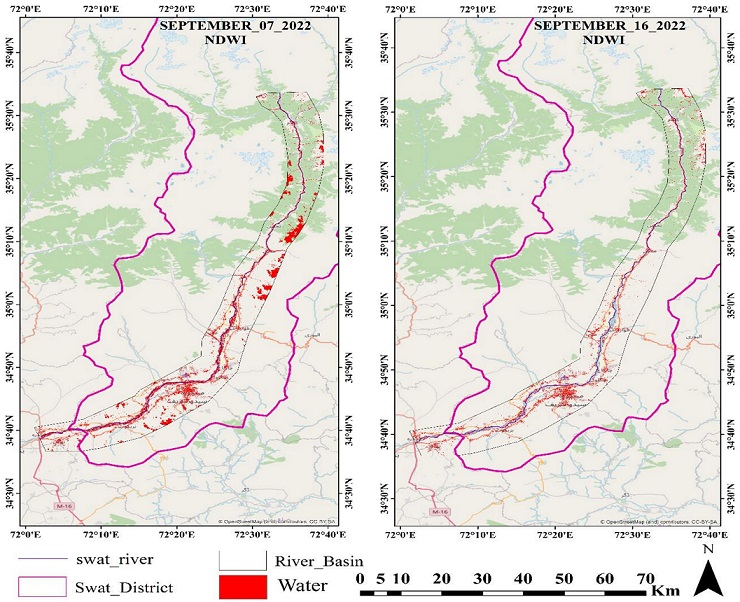

NDWI for September-2022:

In the analysis of post-flood Sentinel-2 imagery for September, two images taken on the

6th and 16th of September were examined to assess the persistence of floodwater in the study

area. The purpose was to determine whether the floodwaters had receded or if any residual water

remained in the affected regions. The image acquired on the 6th of September indicated an

overall water extent of approximately 6,514 hectares, which accounts for around 6% of the total

basin area. The areas that were still affected by floodwaters were Mangora, Saidu Sharif, and

some parts of Mangora. The presence of water in these areas could be attributed to their

relatively fewer sloping surfaces, which may have caused water to accumulate and linger for a

longer duration compared to other parts of the river basin. Moving to the image obtained on

the 16th of September, it was observed that the affected areas still exhibited water presence.

However, the extent of the floodwater had decreased to approximately 2,520 hectares, which

accounts for about 2% of the total basin area. This reduction in the affected area suggests that

the floodwaters were gradually receding [8].

Figure 3: Spatial -temporal flood area extent for September month using the NDWI

These trends in the post-flood imagery demonstrate the effectiveness of using the

NDWI for water detection in flooded areas. The index successfully identified the presence of

water, even in the post-flood stage. However, it is important to note that the persistence of cloud cover and other factors can influence the accuracy and interpretation of the results. The

persistent presence of water in the areas of Mangora, Saidu Sharif, and parts of Manglor in both

images can be attributed to their topographical characteristics, such as flat or less sloping terrain.

These areas are more prone to water accumulation and slower drainage, resulting in a longer

duration of water presence. The analysis of September imagery highlights the importance of

considering post-flood water extent to assess the duration and persistence of floodwaters [19].

The NDWI index proved effective in identifying water presence, and the observed trends

provide valuable insights into the dynamics of the floodwaters in the study area. However, it is

crucial to acknowledge the influence of cloud cover and other factors that may affect the

accuracy and interpretation of the results. Figure 1, 2 and 3 illustrates the spatial temporal flood

area extent for the months of July, August and September respectively using NDWI.

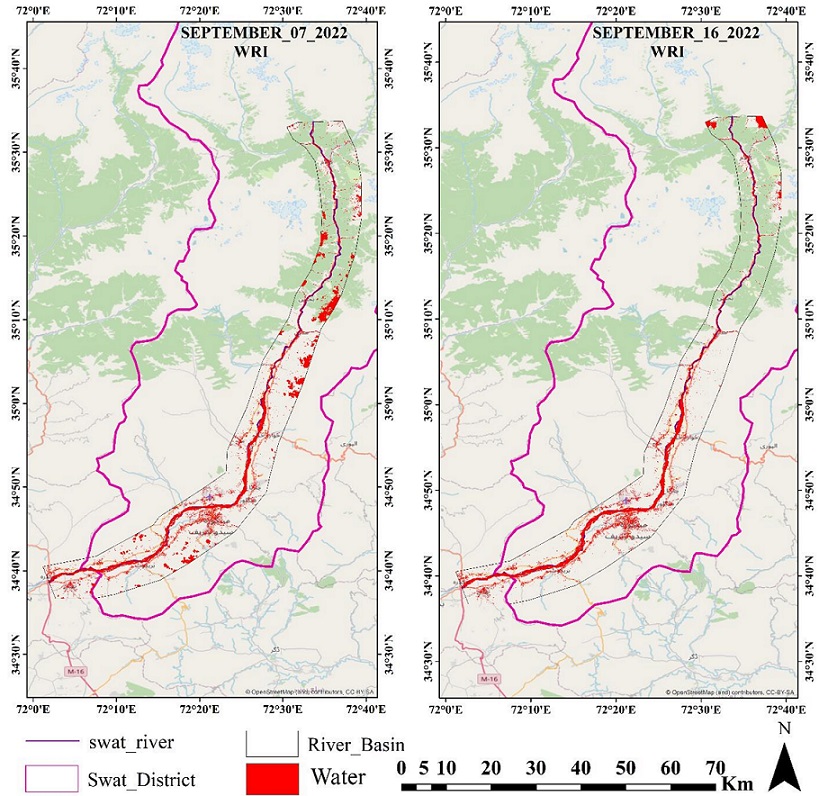

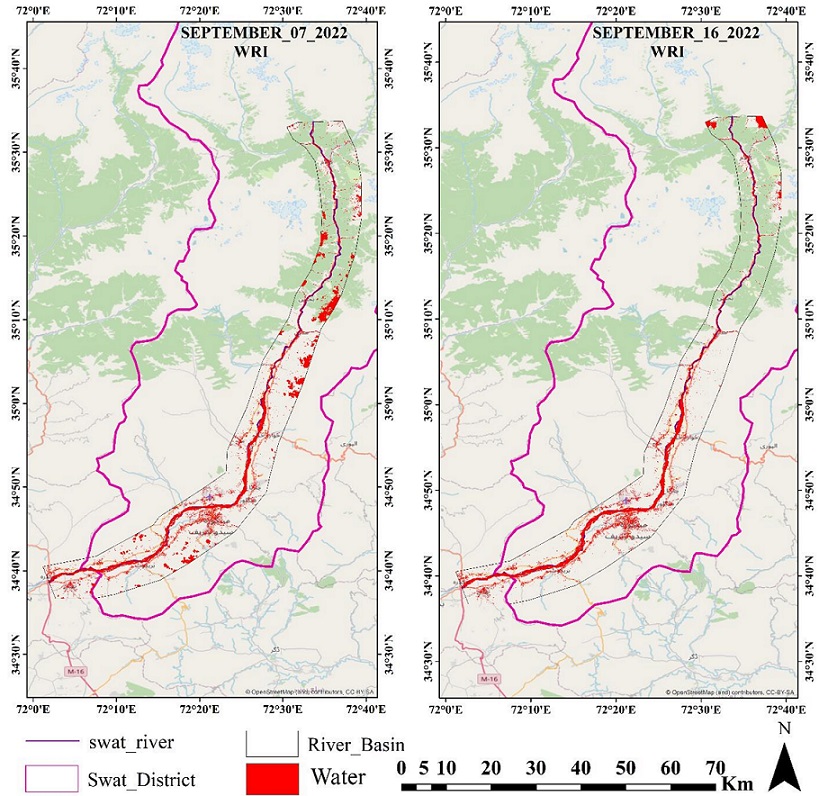

The Water Ratio Index (WRI):

In addition to the NDWI , the WRI (Water Ratio Index) was also calculated and analyzed

to further assess the water extent and dynamics in the study area. The WRI index provides

valuable insights into the water distribution and variability, allowing for a more comprehensive

understanding of the flood event. The following sections present the results obtained from the

analysis of the WRI index, including the interpretation of the images and the identification of

water-affected areas [20].

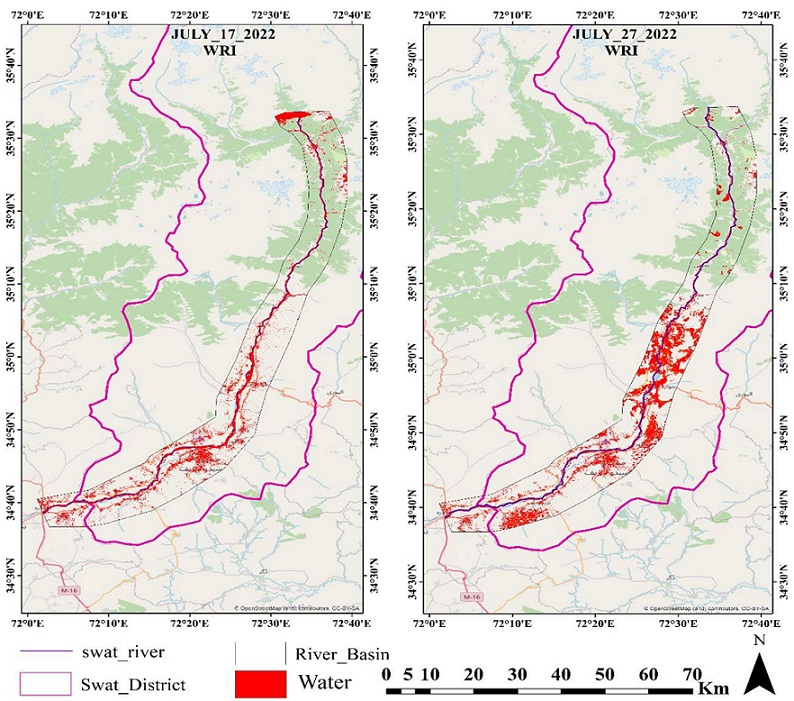

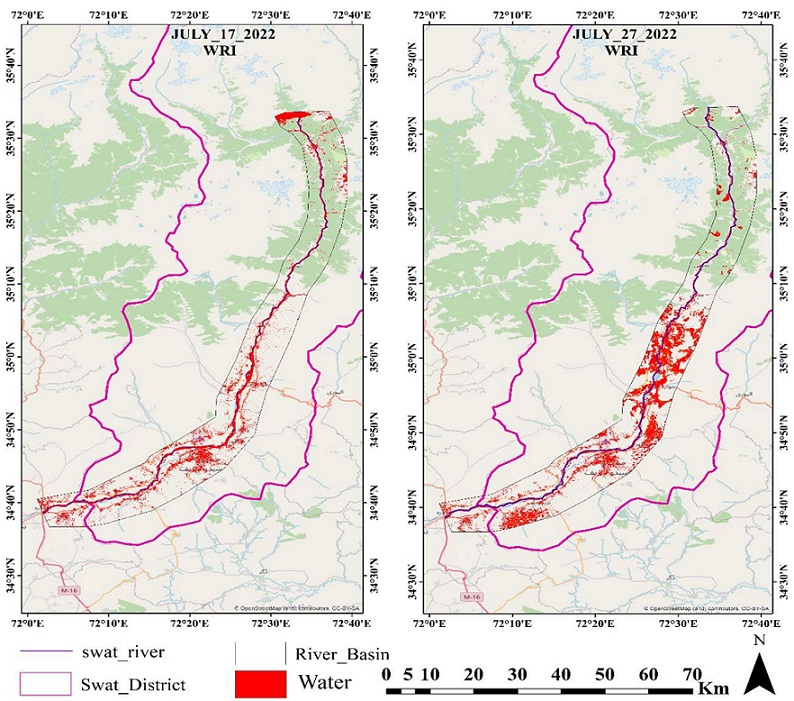

WRI for July-2022:

In the analysis of the WRI images, it was observed that the water extent indicated by the

WRI index was generally higher than that of the NDWI. For the image acquired on the 17th of

July, the WRI index indicated a water extent of approximately 4,573 hectares, which is higher

than the water extent observed using the NDWI index. The most affected regions by the

floodwaters were Charbagh, Manglor, Mangora, Saidu Sharif, and Chakdara. Compared to the

NDWI index, the WRI index showed a higher water extent of around 2% of the total basin area.

Moving to the image obtained on the 27th of July, the water extent increased from 7,565 hectares

(as indicated by the NDWI index) to 9,432 hectares (9% of the total basin area) when using the

WRI index. The areas most affected by the floodwaters remained the same as observed in the

NDWI analysis, including Mangora and Saidu Sharif, followed by Charbagh and Khwazakhela

[21]. These findings suggested that the WRI index provides a more extensive representation of

the water extent compared to the NDWI index. The higher water extent observed in the WRI

analysis can be attributed to the inclusion of additional spectral bands (Green and Red) in the

calculation of the index. These bands contribute to a more comprehensive assessment of water

presence, especially in flood-affected regions.

The agreement between the affected areas identified by both the NDWI and WRI

indices further supports the reliability of these indices for flood mapping and water extent

analysis. The consistency in the most affected regions, such as Mangora, Saidu Sharif, Charbagh,

and Khwazakhela, underscores the reliability of the indices in capturing the spatial distribution

of floodwaters. The incorporation of the WRI index in the analysis enhances the assessment of

water extent during flood events [22]. The index demonstrates its effectiveness in identifying

and mapping flood-affected areas, with a larger water extent observed compared to the NDWI

index. The findings highlighted the importance of utilizing multiple indices for a comprehensive

understanding of flood dynamics and their impacts on the study area.

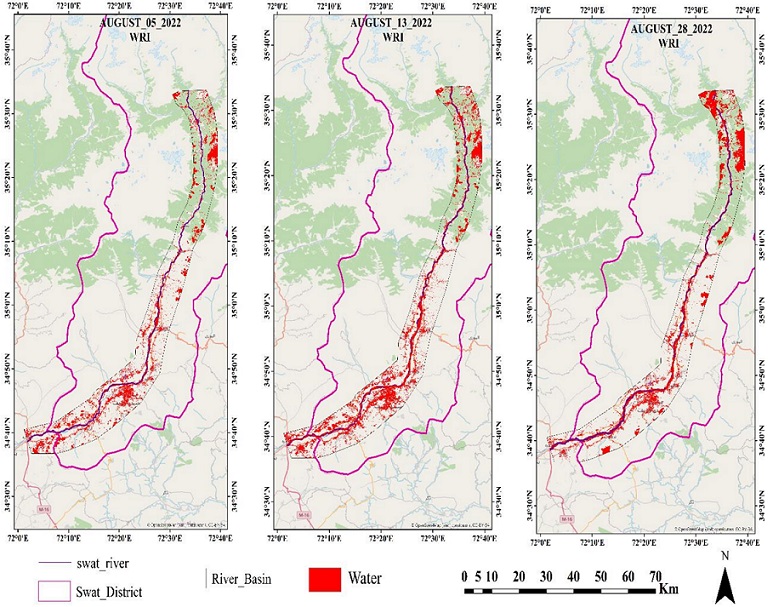

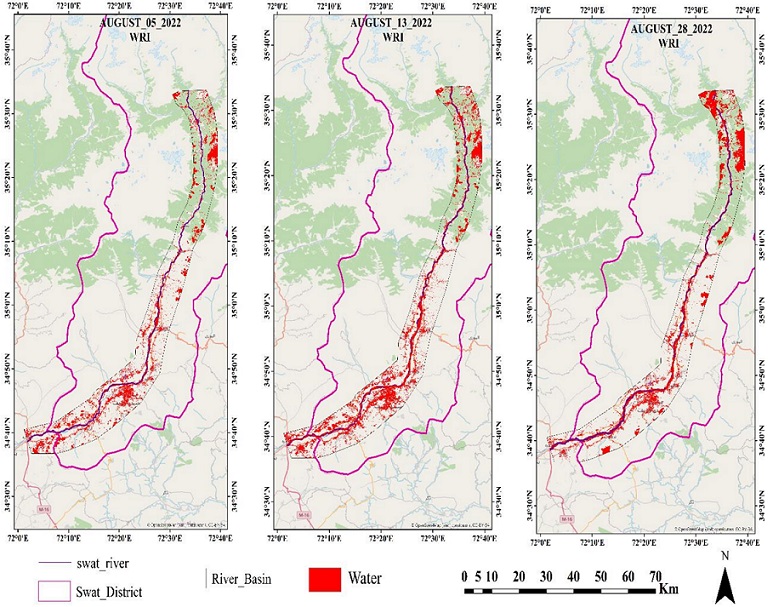

WRI for August-2022:

In the analysis of the WRI images for the month of August, which is known to be the

most flooded month, the results showed similar trends to those observed in the NDWI analysis.

For the image acquired on the 5th of August, both the WRI and NDWI indices indicated a water

extent of approximately 9,519 hectares, accounting for around 9% of the total basin area. The

most affected areas identified in this image were Mangora and Saidu Sharif, indicating localized flooding in these regions. The agreement between the WRI and NDWI results suggests the

consistency in identifying flood-affected areas during this period [23].

Figure 4: Spatial -temporal flood area extent for July month using the WRI.

Moving to the image acquired on the 13th of August, the water extent increased from

9,572 hectares (NDWI) to 12,962 hectares (3% increase) when using the WRI index. Mangora

and Saidu Sharif remained highly affected, and the flood extent expanded to other areas,

including Charbagh, Manglor, Barikot, and Chakdara. The WRI analysis captured the spatial

dynamics of floodwaters, demonstrating its effectiveness in identifying the expansion of floodaffected regions compared to the NDWI analysis. For the final image acquired on the 28th of

August, the water extent decreased from 22,602 hectares (21% of the total basin area) to 16,223

hectares (15% decrease) when using the WRI index. The most heavily affected areas shifted to

Kalam and Bahrain, with substantial flooding observed in these regions. It is worth noting that,

unlike the NDWI analysis, the WRI index also indicated the impact of flooding in Chakdara,

highlighting the importance of incorporating additional spectral bands in the index calculation

[24]. Figure 4 and 5 shows spatial-temporal flood are extent for the months of July and August

respectively using WRI.

Figure 5: Spatial -temporal flood area extent for August month using the WRI

The results emphasized the capability of the WRI index in capturing the changes in flood

extent and identifying the most affected areas. The agreement between the WRI and NDWI

analyses confirms the reliability of both indices in mapping floodwaters. The observed

differences in the affected areas between the two indices highlighted the complementary nature

of the WRI index, which provides additional insights into the spatial distribution of floodwaters

and enhances the overall understanding of flood dynamics in the study area. In summary, the

WRI index proved valuable in assessing the water extent during the highly flooded month of

August. It effectively identified and mapped flood-affected areas, showing consistency with the

results obtained from the NDWI analysis. The inclusion of additional spectral bands in the WRI

index calculation contributed to a comprehensive assessment of flood dynamics, capturing

localized flooding and the expansion of flood extents in different regions [25].

WRI for post flood month (September-2022):

In September, the post-flood period, two images were obtained on the 6th and 16th of

the month to assess the persistence of floodwaters. The results obtained from the WRI analysis

revealed the presence of water in the study area, indicating the potential residual impacts of the

floods.

Figure 6: Spatial -temporal flood area extent for September month using the WRI

For the image acquired on the 6th of September, the WRI index identified an area of

approximately 7,834 hectares (7% of the total basin area) still covered by water. This was slightly

higher than the area identified using the NDWI, which was 6%. The areas that were still affected

by floodwaters included Mangora, Saidu Sharif, and some parts of Manglor. The persistence of

water in these areas could be attributed to their fewer sloping surfaces compared to other parts

of the river basin, which hindered the rapid drainage of floodwaters. Moving to the image

acquired on the 16th of September, it was observed that approximately 2,732 hectares (2.5%) of

the area were still affected by floodwaters according to the WRI analysis. This was higher than

the area identified using the NDWI analysis, which was 2,520 hectares. In above figure 6, it was

notable that some areas of Kalam, which were missing in the NDWI analysis, were still affected by floodwaters. Additionally, Mangora and Barikot were identified as the most affected areas

using this image.

The results of the WRI analysis in the post-flood period highlight the persistence of

floodwaters in certain areas, indicating the slower drainage and accumulation of water in regions

with less sloping terrain. The WRI index provided valuable information on the extent of water

coverage, supplementing the findings from the NDWI analysis. The differences observed in the

affected areas between the WRI and NDWI indices highlight the importance of considering

multiple indices to gain a comprehensive understanding of post-flood conditions. Overall, the

results demonstrated that the WRI index effectively captured the presence of water in the postflood period, allowing for the identification of areas still affected by floodwaters. This

information contributes to a better understanding of the long-lasting impacts of floods and helps

in assessing the recovery and resilience of the study area in the aftermath of flooding events.

Flood Inundation Using Sentinel-1:

In addition to the flood extent maps derived from Sentinel-2 data using the NDWI and

WRI indices, flood inundation maps were also generated using Sentinel-1 data. The Sentinel-1

data provides valuable information on flood conditions, especially in areas with high cloud cover

or during nighttime when optical sensors are limited. For the flood inundation mapping using

Sentinel-1 data, a total of 15 images were acquired for each month, including July, August, and

September. These images were processed and filtered using speckle filtering techniques to

reduce noise and enhance the visibility of flood signals. The filtered images were then combined

using the mosaic function to create a single image representing the flood extent for each month.

The mosaic function effectively merges multiple Sentinel-1 images to generate a composite

image that reflects the cumulative flood extent over the respective month. This approach allows

for a comprehensive representation of the flood conditions during the specific time periods.

The flood inundation maps generated from Sentinel-1 data provide additional insights

into the spatial distribution of floodwaters, complementing the information derived from

Sentinel-2 data. The inclusion of Sentinel-1 data enhances the accuracy and reliability of the

flood extent assessment, especially in challenging conditions such as high cloud cover or in areas

with dense vegetation. By integrating the flood inundation maps from both Sentinel-1 and

Sentinel-2 data, a more comprehensive understanding of the flood dynamics and the extent of

water coverage can be obtained. This multi-sensor approach improves the reliability and

robustness of the flood mapping results, enabling better-informed decision-making and flood

management strategies.

The flood inundation maps generated from Sentinel-1 data, in combination with the

NDWI and WRI indices derived from Sentinel-2 data, provided a comprehensive assessment of

the flood conditions in the study area. These maps contribute to the understanding of the spatial

and temporal variations in flood extent, helping to identify the most affected areas and assess

the overall impact of the floods on the region. It is worth noting that the utilization of both

Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data sets and the integration of various indices and flood mapping

techniques contribute to a more accurate and comprehensive analysis of the flood events. This

multi-sensor and multi-index approach enhances the reliability and effectiveness of flood

monitoring and assessment, supporting decision-makers and stakeholders in implementing

appropriate mitigation and adaptation measures.

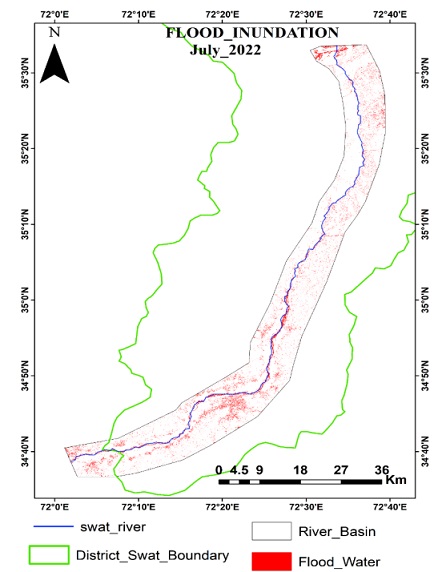

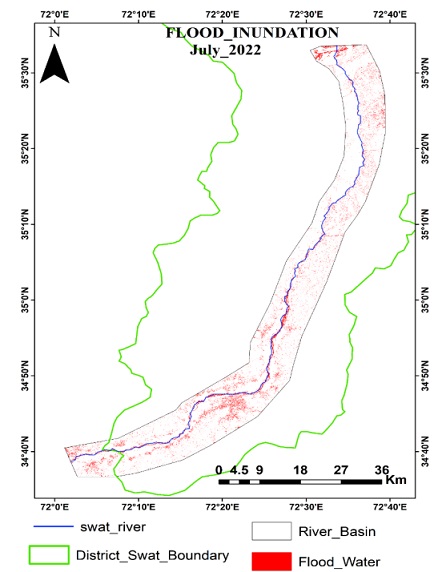

Flood Inundation Extant for July-2022:

The flood inundation mapping using Sentinel-1 data for the month of July revealed a

total flood area of approximately 12982 hectares, accounting for approximately 12% of the study

area as indicated in figure 7. This information was obtained by creating a mosaic of all 15

available images from Sentinel-1 and utilizing the IW (Interferometric Wide) and VH

(Vertical/Horizontal) polarization bands in Google Earth Engine. The analysis of the flood inundation map indicated that the areas most affected by the floods were Kalam, Bahrain,

Mangora, Saidu Sharif, Barikot and Madyan. These regions are characterized by high altitudes,

which can contribute to increased susceptibility to flooding due to steep terrain and higher water

runoff. Conversely, the lower altitude areas within the study area were relatively less affected by

the floods. By incorporating the Sentinel-1 data, which is based on radar technology, the flood

extent mapping provides additional insights into the areas affected by the floods. Radar data is

less influenced by atmospheric conditions, such as cloud cover, and can penetrate through

vegetation, allowing for a more accurate assessment of flood extent.

Figure 7: Sentinel-1 Flood Inundation Map for July-200

The inclusion of high-altitude areas, such as Kalam, Bahrain, and Madyan, among the

most affected regions highlights the role of topography in influencing flood dynamics. The steep

slopes and narrow valleys in these areas can exacerbate the flow of water, leading to increased

flood inundation. Overall, the integration of Sentinel-1 data in the flood inundation mapping

enhances the understanding of the spatial distribution of floodwaters and helps identify the areas

that are most susceptible to flooding. This information can be valuable for disaster management

and planning authorities to implement appropriate measures for flood mitigation and

preparedness in the affected regions.

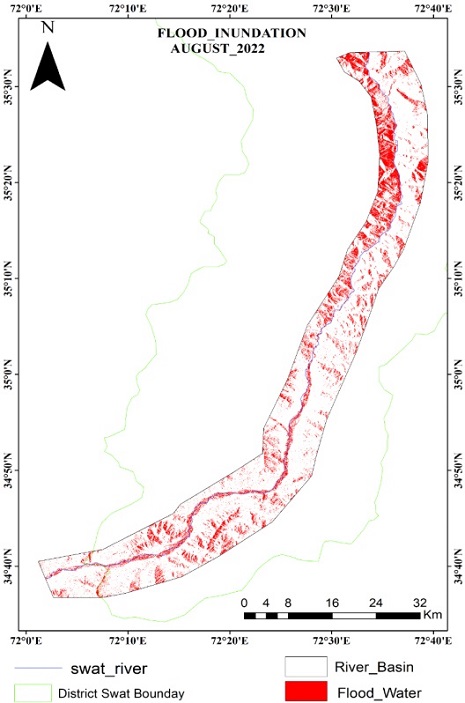

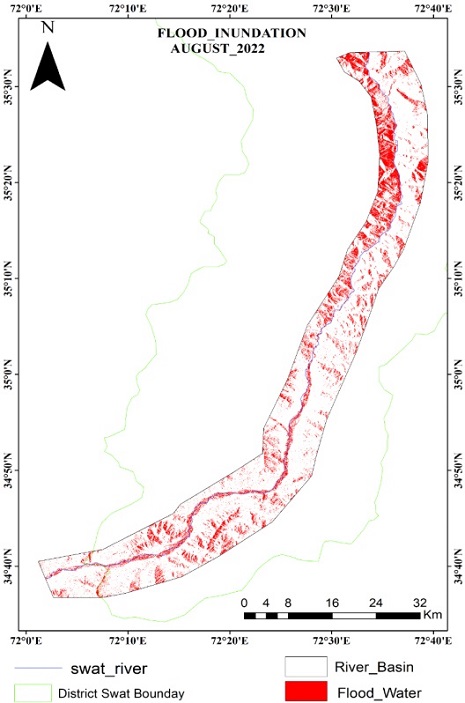

Flood Inundation Extant for August-2022:

In the case of flood inundation mapping for the month of August, the mosaic of all the

available images from Sentinel-1 revealed a significant extent of flooding. The analysis of this

map indicates that approximately 40% of the study area, accounting for about 43,126 hectares,

was experiencing floods during this period. The flood extent map clearly depicts the severity of

the floods, with many locations experiencing severe to extreme flood conditions. Among the most affected areas, Kalam stands out as the region experiencing the highest flood extent.

Following Kalam, areas such as Bahrain, Madyan, Mangora, Saidu Sharif, and Barikot also

experienced high flood events.

The high flood levels in Kalam, Bahrain, and Madyan highlight the vulnerability of these

regions to intense flooding. Factors such as steep terrain, narrow valleys, and high rainfall

intensity contribute to the heightened flood risk in these areas. The presence of such severe

flood conditions indicates the potential for significant damage to infrastructure, agriculture, and

livelihoods in these regions. The flood extent in Mangora, Saidu Sharif, and Barikot also reached

significant levels, indicating widespread inundation in these areas. The severity of the floods

underscores the importance of comprehensive flood management strategies and early warning

systems to mitigate the potential impacts on communities and infrastructure. Figure 8 shows

Sentinel 1 flood induction map for August 2002.

Figure 8: Sentinel-1 Flood Inundation Map for August-2002

By utilizing the Sentinel-1 data and generating the flood inundation map for August, a

detailed understanding of the spatial distribution and severity of the floods can be obtained. This

information is crucial for disaster response and recovery efforts, as it enables targeted

interventions and resource allocation to the most affected areas. Overall, the flood inundation

mapping for August highlights the widespread nature of the floods, with a significant portion of

the study area experiencing severe inundation. This information can support decision-makers and disaster management authorities in developing effective strategies for flood mitigation,

preparedness, and response in the affected regions.

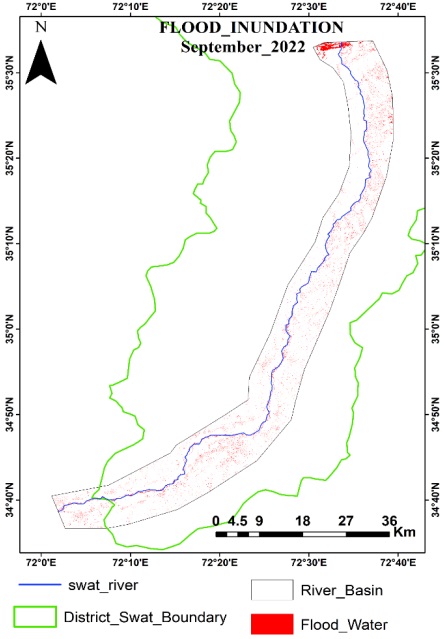

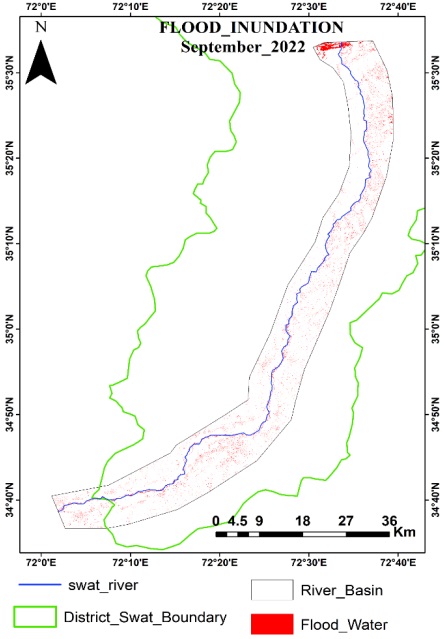

Flood Inundation Extant for September-2022:

In the month of September, which is the post-flood period, the flood inundation

mapping using Sentinel-1 data indicated that an area of approximately 6,624 hectares, accounting

for approximately 6% of the total study area, remained under flood extent as indicated in figure

9. This information was obtained by analyzing a mosaic image generated from the 15 available

Sentinel-1 images for the month of September. The analysis of the flood extent in the post-flood

month provides insights into the persistence of floodwaters and the areas that are still affected.

High-altitude regions such as Kalam, Bahrain, and Madyan were observed to still have

floodwaters, indicating the slow receding process in these areas. On the other hand, low-lying

areas experienced a relatively lower impact and were less affected by the floodwaters during this

period.

The inclusion of Sentinel-1 data in the flood inundation mapping allows for the

identification and monitoring of post-flood water bodies, aiding in the assessment of the flood

recovery process. This information is valuable for understanding the long-term impacts of

flooding and facilitating appropriate measures for rehabilitation and mitigation efforts in the

affected areas. By combining the flood inundation maps from different months and sources, a

comprehensive understanding of the flood dynamics and their impacts on different regions can

be obtained. This integrated approach facilitates a better assessment of the flood situation and

aids in decision-making processes for effective flood management and mitigation strategies.

Figure 9: Sentinel-1 Flood Inundation Map for September-2002

The discussion section aims to interpret and analyze the obtained results in relation to

the research question and objectives. The primary objective of the study was to assess the

effectiveness of using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data for flood monitoring and mapping, specifically focusing on the accuracy and reliability of these remote sensing techniques in

identifying flood inundation areas. The analysis was conducted using water indices, including

NDWI and WRI, to extract floodwater areas and generate flood inundation maps. The selection

of images with low cloud cover was crucial to ensure high-quality and cloud-free imagery for

accurate flood extent estimation. The strategy of selecting days with minimal cloud cover based

on historical patterns and climatic conditions specific to the study area aimed to minimize

misclassification and ambiguity in identifying flooded areas. By minimizing the impact of cloud

cover, the research aimed to enhance the precision and quality of the derived flood extent maps,

enabling more robust flood monitoring and management. The results obtained from the NDWI

analysis for July 2022 revealed important insights into the extent and intensity of flooding in the

study area. The images captured on 17th July and 27th July showed a progressive intensification

of the flood event, with a larger area being affected by floodwaters on 27th July. The identified

areas of Charbagh, Mangora, Saidu Sharif, and Chakdara consistently showed high vulnerability

to flooding, indicating the need for focused flood management and mitigation measures in these

regions.

Moving to the analysis of the NDWI images for August 2022, the results demonstrated

the temporal variation and spatial distribution of floodwater extent. The images captured on 5th

August, 13th August, and 28th August provided valuable insights into the increasing water extent

and the most affected areas. The analysis showed that Mangora and Saidu Sharif remained highly

affected throughout the month, while the flood extent expanded to other areas such as

Charbagh, Manglor, Barikot, and Chakdara. The progressive increase in the extent and intensity

of the floodwaters emphasized the need for targeted flood mitigation measures in these areas.

In September 2022, the post-flood period, the analysis of NDWI images on 6th September and

16th September indicated the persistence of floodwaters in certain areas. Mangora, Saidu Sharif,

and some parts of Manglor were still affected, suggesting the slower drainage and accumulation

of water in regions with less sloping terrain. The findings highlighted the effectiveness of the

NDWI index in identifying water presence, even in the post-flood stage, but acknowledged the

influence of cloud cover and other factors on the accuracy and interpretation of the results. The

results obtained from the WRI analysis complemented the findings from the NDWI analysis,

providing additional insights into the water distribution and variability. The WRI index showed

a higher water extent compared to the NDWI index, indicating its effectiveness in capturing the

spatial dynamics of floodwaters. The agreement between the affected areas identified by both

indices further supported their reliability for flood mapping and water extent analysis.

The flood inundation maps generated from Sentinel-1 data using IW and VH

polarization bands provided additional insights into the spatial distribution of floodwaters. The

analysis revealed significant flood extents in July, August, and September 2022, with highaltitude areas such as Kalam, Bahrain, and Madyan experiencing the highest flood levels. The

integration of Sentinel-1 data enhanced the accuracy and reliability of the flood extent

assessment, particularly in challenging conditions such as high cloud cover or dense vegetation.

In conclusion, the results obtained from the analysis of Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-1 data using

NDWI, WRI, and flood inundation mapping techniques provided valuable information on the

extent, intensity, and spatial distribution of floodwaters in the study area. The findings

demonstrated the effectiveness of remote sensing techniques in flood monitoring and mapping,

allowing for better-informed decision-making processes related to emergency response, resource

allocation, and long-term flood mitigation strategies. The study highlighted the importance of

considering multiple indices and satellite data sources for a comprehensive understanding of

flood dynamics, while acknowledging the influence of cloud cover and other factors on the

accuracy of the results.

Conclusion

This research aimed to assess the effectiveness ofSentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data for flood

monitoring and mapping. Through the application of water indices such as NDWI and WRI,

combined with the analysis of flood inundation maps, generated from Sentinel-1 data, valuable

insights into the spatial distribution and extent of floodwaters were obtained. The results of the

study indicated that both Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data are reliable and effective sources for

flood monitoring and mapping. The NDWI and WRI indices derived from Sentinel-2 data

successfully identified and mapped flood-affected areas, providing valuable information on the

extent and intensity of flooding events. The inclusion of Sentinel-1 data enhanced the accuracy

and reliability of the flood extent assessments, particularly in challenging conditions such as high

cloud cover or dense vegetation.

The analysis of the flood extent maps revealed specific areas that are highly vulnerable

to intense flooding. Regions such as Kalam, Bahrain, Madyan, Mangora, Saidu Sharif, and

Barikot consistently experienced significant flood extents, indicating the need for focused flood

management and mitigation measures in these areas. The topographical characteristics of steep

terrain, narrow valleys, and high rainfall intensity contribute to the heightened flood risk in these

regions. The findings from this research contribute to a better understanding of flood dynamics

and their impacts on the study area. The integration of multiple indices and satellite data sets

allows for a comprehensive assessment of flood events, enabling informed decision-making

processes for emergency response planning, resource allocation, and the implementation of

effective flood mitigation strategies.

Reference

[1] R. Sivanpillai, K. M. Jacobs, C. M. Mattilio, and E. V Piskorski, “Rapid flood inundation

mapping by differencing water indices from pre- and post-flood Landsat images,” Front.

Earth Sci., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2021, doi: 10.1007/s11707-020-0818-0.

[2] P. Zhang et al., “Hydrodynamic and Inundation Modeling of China’s Largest Freshwater

Lake Aided by Remote Sensing Data,” Remote Sens., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 4858–4879, 2015,

doi: 10.3390/rs70404858.

[3] B. Khalid et al., “Riverine flood assessment in Jhang district in connection with ENSO

and summer monsoon rainfall over Upper Indus Basin for 2010,” Nat. Hazards, vol. 92,

no. 2, pp. 971–993, 2018, doi: 10.1007/s11069-018-3234-y.

[4] A. Refice et al., “SAR and InSAR for flood monitoring: Examples with

COSMO/SkyMed data,” Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sensing, IEEE J., vol. 7,

2014, doi: 10.1109/JSTARS.2014.2305165.

[5] N. W. Arnell and S. N. Gosling, “The impacts of climate change on river flood risk at

the global scale,” Clim. Change, vol. 134, no. 3, pp. 387–401, 2016, doi: 10.1007/s10584-

014-1084-5.

[6] S. M. El-Hadidy and S. M. Morsy, “Expected spatio-temporal variation of groundwater

deficit by integrating groundwater modeling, remote sensing, and GIS techniques,”

Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Sp. Sci., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 97–111, 2022, doi:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrs.2022.01.001.

[7] D. S. Williams, M. Máñez Costa, L. Celliers, and C. Sutherland, “Informal Settlements

and Flooding: Identifying Strengths and Weaknesses in Local Governance for Water

Management,” Water, vol. 10, no. 7, 2018, doi: 10.3390/w10070871.

[8] L. Tascón-González, M. Ferrer-Julià, M. Ruiz, and E. García-Meléndez, “Social

Vulnerability Assessment for Flood Risk Analysis,” Water, vol. 12, no. 2. 2020. doi:

10.3390/w12020558.

[9] K. Uddin, M. A. Matin, and F. J. Meyer, “Operational Flood Mapping Using MultiTemporal Sentinel-1 SAR Images: A Case Study from Bangladesh,” Remote Sens., vol 11, no. 13, 2019, doi: 10.3390/rs11131581.

[10] V. Scotti, M. Giannini, and F. Cioffi, “Enhanced flood mapping using synthetic aperture

radar (SAR) images, hydraulic modelling, and social media: A case study of Hurricane

Harvey (Houston, TX),” J. Flood Risk Manag., vol. 13, no. 4, p. e12647, Dec. 2020, doi:

10.1111/JFR3.12647.

[11] C. Șerban, C. Maftei, and G. Dobrică, “Surface Water Change Detection via Water

Indices and Predictive Modeling Using Remote Sensing Imagery: A Case Study of

Nuntasi-Tuzla Lake, Romania,” Water 2022, Vol. 14, Page 556, vol. 14, no. 4, p. 556,

Feb. 2022, doi: 10.3390/W14040556.

[12] R. O. Salami, J. K. von Meding, and H. Giggins, “Vulnerability of human settlements to

flood risk in the core area of Ibadan metropolis, Nigeria.,” Jamba (Potchefstroom,

South Africa), vol. 9, no. 1, p. 371, 2017, doi: 10.4102/jamba.v9i1.371.

[13] J. Serrano, S. Shahidian, and J. M. da Silva, “Evaluation of Normalized Difference Water

Index as a Tool for Monitoring Pasture Seasonal and Inter-Annual Variability in a

Mediterranean Agro-Silvo-Pastoral System,” Water 2019, Vol. 11, Page 62, vol. 11, no.

1, p. 62, Jan. 2019, doi: 10.3390/W11010062.

[14] Q. Shenming, L. Xiang, and G. Zhihua, “A new hyperspectral image classification

method based on spatial-spectral features,” Sci. Reports 2022 121, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–

16, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05422-5.

[15] A. Rahadiati, M. Munawaroh, and E. Suryanegara, “The Impact of Flooding on

Settlement Along the Jangkok River Mataram, Indonesia,” IOP Conf. Ser. Earth

Environ. Sci., vol. 750, p. 12003, 2021, doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/750/1/012003.

[16] Q. Sholihah, W. Kuncoro, S. Wahyuni, S. Puni Suwandi, and E. Dwi Feditasari, “The

analysis of the causes of flood disasters and their impacts in the perspective of

environmental law,” IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 437, no. 1, p. 012056, Feb.

2020, doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/437/1/012056.

[17] R. Sivanpillai, K. M. Jacobs, C. M. Mattilio, and E. V. Piskorski, “Rapid flood inundation

mapping by differencing water indices from pre- and post-flood Landsat images,” Front.

Earth Sci., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Mar. 2021, doi: 10.1007/S11707-020-0818-

0/METRICS.

[18] Syam’Ani, “Capability of Sentinel-1 Synthetic Aperture Radar polarimetric change

detection for burned area extraction in South Kalimantan, Indonesia,” IOP Conf. Ser.

Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 500, no. 1, p. 012004, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.1088/1755-

1315/500/1/012004.

[19] C. W. J. Tay, S. H. Yun, S. T. Chin, A. Bhardwaj, J. Jung, and E. M. Hill, “Rapid flood

and damage mapping using synthetic aperture radar in response to Typhoon Hagibis,

Japan,” Sci. Data 2020 71, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-

0443-5.

[20] A. Sharifi, H. Mahdipour, E. Moradi, and A. Tariq, “Agricultural Field Extraction with

Deep Learning Algorithm and Satellite Imagery,” J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens., vol. 50,

no. 2, pp. 417–423, Feb. 2022, doi: 10.1007/S12524-021-01475-7/METRICS.

[21] K. Uddin, M. A. Matin, and F. J. Meyer, “Operational Flood Mapping Using MultiTemporal Sentinel-1 SAR Images: A Case Study from Bangladesh,” Remote Sens. 2019,

Vol. 11, Page 1581, vol. 11, no. 13, p. 1581, Jul. 2019, doi: 10.3390/RS11131581.

[22] A. Verhegghen et al., “The Potential of Sentinel Satellites for Burnt Area Mapping and

Monitoring in the Congo Basin Forests,” Remote Sens. 2016, Vol. 8, Page 986, vol. 8,

no. 12, p. 986, Nov. 2016, doi: 10.3390/RS8120986.

[23] W. Nigel, “Integrated river basin management: A case for collaboration,” Int. J. River

Basin Manag., vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 243–257, 2004, doi: 10.1080/15715124.2004.9635235.

[24] H. Waqas et al., “Flash Flood Susceptibility Assessment and Zonation Using an

Integrating Analytic Hierarchy Process and Frequency Ratio Model for the Chitral

District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan,” Water 2021, Vol. 13, Page 1650, vol. 13, no.

12, p. 1650, Jun. 2021, doi: 10.3390/W13121650.

[25] D. S. Williams, M. M. Costa, L. Celliers, and C. Sutherland, “Informal Settlements and

Flooding: Identifying Strengths and Weaknesses in Local Governance for Water

Management,” Water 2018, Vol. 10, Page 871, vol. 10, no. 7, p. 871, Jun. 2018, doi:

10.3390/W10070871.