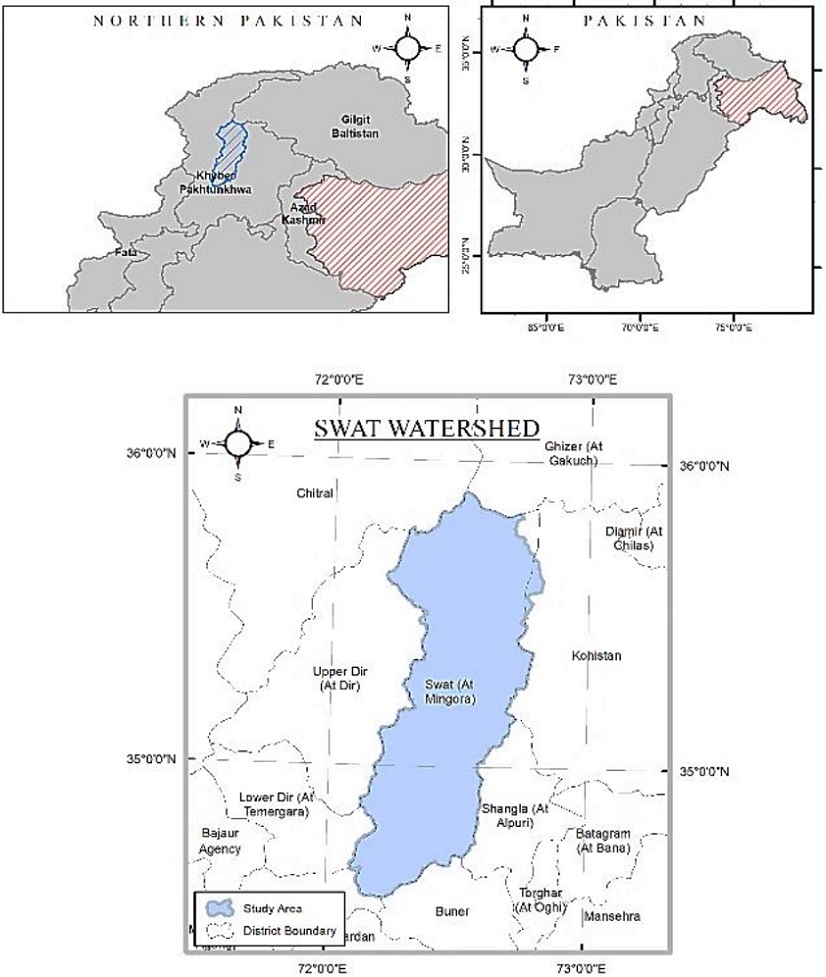

Findings of the DEM analysis conducted in our designated study area indicate a

notable variation in elevation, encompassing a range of 677 meters to 6,000 meters above the

mean sea level (Figure 2). The considerable range in land elevation plays a pivotal role in the

consideration and implementation of dam selection and construction. The DEM data offers

valuable insights into the topographical attributes of the area, facilitating a comprehensive

evaluation of the appropriateness of potential dam locations.

The comprehension of the elevation profile of the study area is crucial in the process

of dam selection. Dams are commonly built in river valleys or canyons, and the utilization of

elevation data aids in the identification of appropriate sites where the natural topography aligns

with the engineering specifications for dam establishment. The presence of diverse elevation

values in the study area enables us to evaluate the viability of various dam types, such as smallscale reservoirs in areas with low elevation or high-head dams in mountainous terrains.

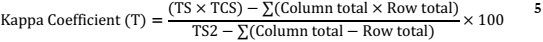

Rainfall Datasets:

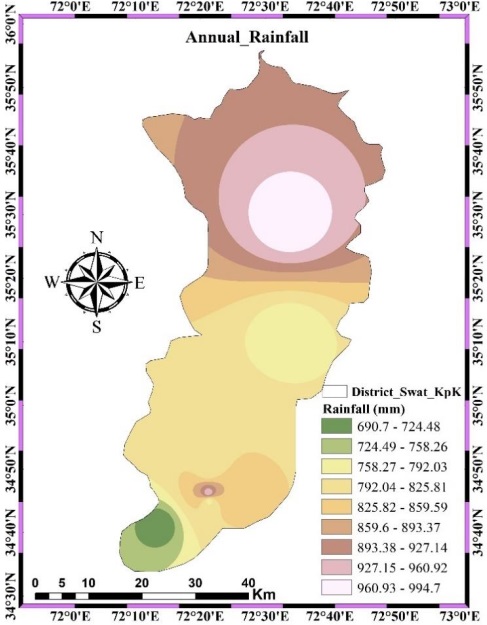

In the context of our study on dam selection, we utilized mean annual rainfall data

collected from multiple weather stations to create a comprehensive rainfall map for the Swat

district. The rainfall values across the entire study area were estimated and interpolated using

the IDW interpolation technique. The procedure enabled the development of comprehensive

rainfall cartography, which effectively illustrates the geographical dispersion of yearly

precipitation. The distribution of annual rainfall values across the Swat district is visually

depicted in Figure 3, showcasing a range that extends from a minimum of 690 mm to a

maximum of 994 mm. The map successfully conveys the diversity in yearly precipitation,

providing valuable insights into the differential rainfall patterns experienced across different

locations within the study area. The provided information holds significant importance in our

dam selection process, as it aids in the identification of potential dam sites by considering both

technical feasibility and the accessibility of water resources. An essential aspect in the

optimization of dam design and operation for various purposes, such as water supply, flood

control, and hydropower generation, is the comprehension of local rainfall patterns. This understanding ensures that the chosen dam sites are in alignment with the hydrological

conditions and land management objectives of the region, thereby promoting harmonious

integration.

Figure 3: Elevation profile of the study area

Land use Land Cover:

Figure 4 depicts a visual representation of the LULC classification in the Swat region.

The classification system demonstrates a high level of efficacy in effectively organizing the

landscape into seven discrete categories, each of which provides valuable and distinct

perspectives on the land utilization patterns within the given region. The classes that have

been identified include bare land, built-up areas, water bodies, natural trees, cropland, snow,

and grassland. The presented figure effectively illustrates the spatial distribution of the

categories, highlighting their relative proportions within the designated study region. It is

worth mentioning that the Swat region consists of various land cover categories. Specifically,

bare land accounts for 12% of the region, while built-up areas occupy 11%. Water bodies

comprise 1% of the region, while natural trees flourish across 16%. Cropland constitutes 3%

of the region, and snow is observed on 1% of the land. Notably, the dominant land cover

category in the Swat region is grassland, encompassing a significant 43% of the entire area.

The comprehensive LULC classification holds significant significance in the context

of our dam selection process. The utilization of remote sensing techniques facilitates the

identification of appropriate dam sites by offering essential information regarding the land

cover attributes of the area. Comprehending the distribution of LULC categories holds

significant importance in evaluating various factors, including land availability, potential

environmental consequences, and the appropriateness of the adjacent topography for the

construction and functioning of dams. Furthermore, it aids in the assessment of the

prospective consequences on indigenous ecosystems and habitats, guaranteeing that the chosen locations for dam construction are in accordance with sustainable land management

goals. The LULC classification plays a fundamental role in the optimization of dam selection,

encompassing technical feasibility and environmental factors.

Figure 4: Mean annual rainfall for the study area.

Figure 5: LULC for the study area

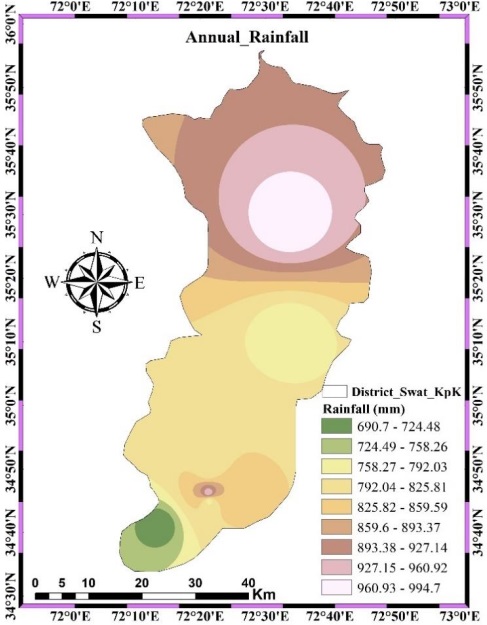

The evaluation of the accuracy of the land cover classification was performed by

employing the Kappa coefficient as a standard measure. By utilizing the SVM algorithm in the

classification procedure, an impressive overall accuracy rate of 89% was attained. The

observed high level of accuracy demonstrates a strong concurrence between the classified

pixels and the ground truth samples, thereby validating the reliability of our classification

outcomes. In addition, it is worth noting that the Kappa coefficient, which goes beyond

random agreement, demonstrates a significant value of 0.87. The high value of the Kappa

coefficient provides strong support for the accuracy of our classification results and increases

confidence in the methodology used.

Soil Analysis:

Distinct colors have been employed in our map to visually depict the various soil types

that are prevalent in the Swat district. Gleysol soils are characterized by a black coloration,

lithosol soils are distinguished by a red coloration, and eutric cambisol soils are identified by a

green coloration. The various soil types are significant in the process of selecting an

appropriate dam site. The selection of a dam site is heavily influenced by soil characteristics,

as the diverse types of soil possess distinct capacities to sustain dam infrastructure and

efficiently regulate water resources. Gleysol soils, characterized by their dark color, frequently

signify elevated levels of moisture and necessitate specific precautions during dam

construction to ensure structural integrity and mitigate seepage. Lithosol soils, illustrated in

red, are commonly characterized by their shallow depth and rocky composition, thereby

exerting potential implications on the design of dam foundations and excavation endeavors. Eutric Cambisol soils, depicted in green, are commonly regarded as highly suitable for the

construction of dams owing to their advantageous characteristics that facilitate strong

foundation support (Figure 5).

A comprehensive understanding of the distribution and characteristics of these soil

types within the Swat district plays a crucial role in the identification of appropriate dam

locations that possess both technical viability and enduring stability. A thorough examination

of soil properties is imperative for minimizing potential hazards and maximizing the

effectiveness of dam design and construction, particularly about water supply, flood

management, and hydropower production.

Figure 6: Soil types in SWAT

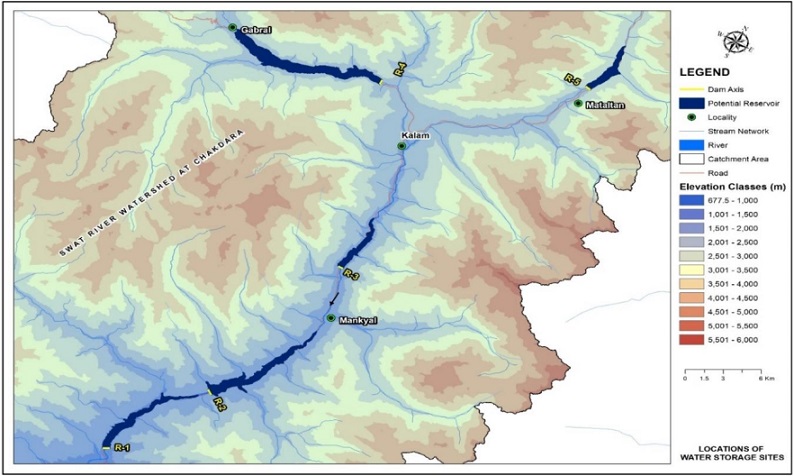

Elevation Area Capacity Curve:

The EAC Curve is a visual depiction that elucidates the correlation between the

elevation of a reservoir's water surface, the corresponding storage volume of water contained

in the reservoir, and the area encompassed by the reservoir at that elevation. The curve serves

as a pivotal instrument for evaluating the viability of dam locations and comprehending the

variations in reservoir storage capacity resulting from fluctuations in water level caused by

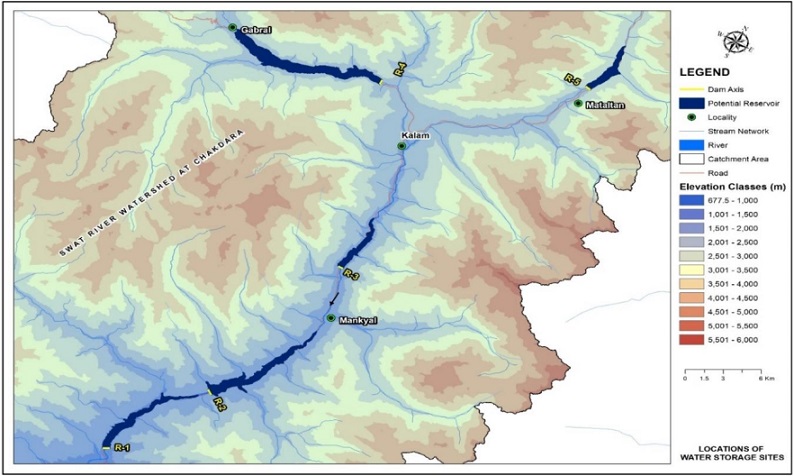

inflow, outflow, and additional factors. In the present study, a total of five distinct potential

dam sites, denoted as R1, R2, R3, R4, and R5, have been identified and are visually represented

in Figure 6. The chosen sites within the study area are strategically positioned, with their

selection being influenced by a range of factors such as topography, hydrology, geology, and

land use. The EAC Curve plays a crucial role in assessing the appropriateness of these locations

for the purpose of constructing dams.

Figure 7: Potential Dam Sites for the study area

Characteristic of Dam Site R1:

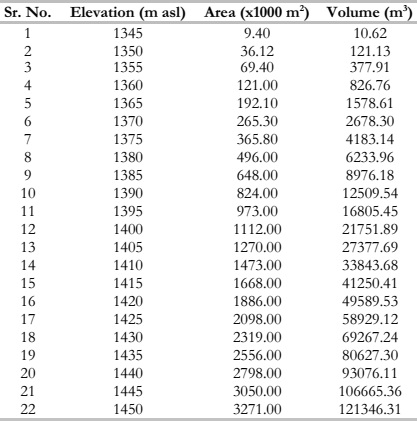

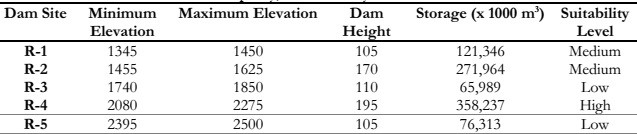

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the characteristics of dam reservoirs at

different elevations. The data presented in this study was obtained using accurate calculations

employing the 3D analyst tool applied to the DEM. The presented table illustrates the

relationship between the elevation of a reservoir, measured in meters above sea level, and the

corresponding alterations in both surface area and storage capacity. As an illustration, situated

at an altitude of 1345m above sea level, the reservoir encompasses an expanse of 9.40 x1000

m² and exhibits a storage capacity of 10.62 m³. Significantly, a rise in altitude from 1345 to

1450ms above sea level results in a considerable enlargement of the reservoir's surface area,

which expands to 3271 x 1000m², accompanied by a noteworthy augmentation in storage

capacity to 121,346 m³. The dataset presented provides significant insights into the direct

influence of various elevations on the physical attributes of the reservoir. These findings can

greatly contribute to informed decision-making processes regarding the planning, design, and

operation of dams.

Figure 7 visually depicts the significant correlation between elevation and the

corresponding area and storage capacity of the dam reservoir. The presented graphical

representation offers a conscious and intuitive comprehension of the impact of variations in

elevation on the physical characteristics of the reservoir. The provided figure visually illustrates

the gradual increase in both the area and capacity of the reservoir as its elevation increases.

For example, it demonstrates the substantial increase in both surface area and storage capacity

that occurs when raising the reservoir's elevation from 1345 to 1450 m above sea level. This

visual aid facilitates the understanding of the direct correlation between elevation and reservoir

characteristics, thereby assisting in the decision-making process for dam design and

management.

Table 1: Reservoir characteristics at dam site R1 (Elevation vs. Area and Volume)

Figure 8: Correlation between elevation, area, and storage capacity for DAM site R1

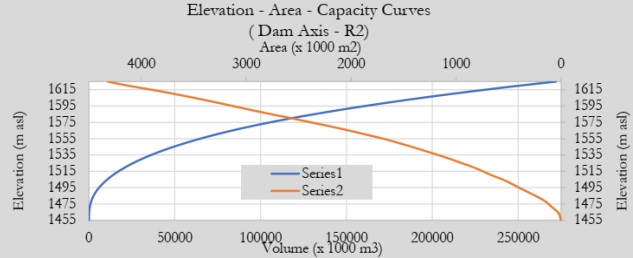

Characteristic of Dam Site R2:

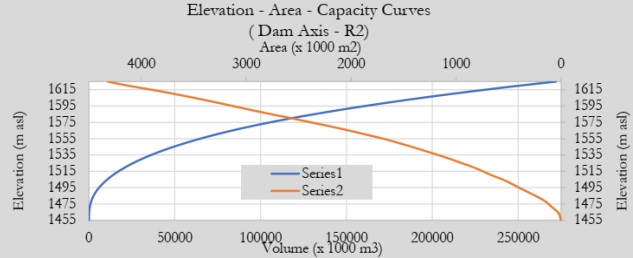

Table 2 and Figure 8 provide essential data pertaining to the reservoir characteristics

of dam site R2 at different elevations. As an illustration, the reservoir demonstrates an

elevation of 1455m above sea level, encompassing an area of 2.91 thousand square meters and

possessing a storage capacity of 2 m3. Significantly, when the elevation is raised to 1625m

above sea level, there is a noteworthy increase in both the area and storage capacity of the

reservoir. Specifically, the reservoir's area expands to 4321x1000 m2, while its storage capacity

experiences a substantial growth to 271,964 m3. These insights play a crucial role in facilitating

well-informed decision-making concerning the planning, design, and management of dam site

R2. They emphasize the direct impact of elevation variations on the physical attributes of the

reservoir.

Table 2: Reservoir characteristics at dam site R2 (Elevation vs. Area and Volume)

Figure 9: Correlation between elevation, area, and storage capacity for DAM site R2

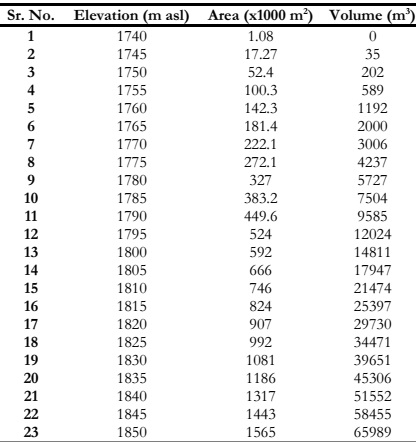

Characteristics of Dam Site R3:

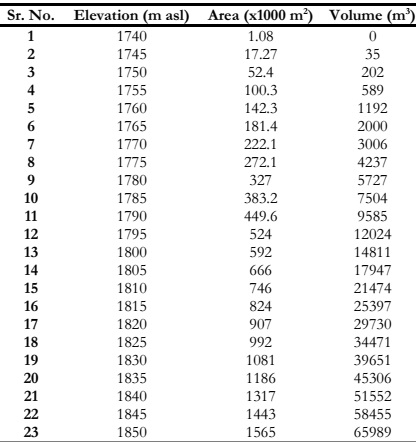

Table 3 and Figure 9 offer significant insights pertaining to the reservoir characteristics

of dam site R3 across various elevations. The data play a crucial role in facilitating wellinformed decision-making processes pertaining to the planning, design, and management of

the site in question. The reservoir, situated at an altitude of 1740m above sea level, demonstrates an area of 1.08 x 1000 m2 and a storage capacity, suggesting a restricted ability

to retain water at this elevation. Nevertheless, when the elevation is raised to 1745m, a

significant transformation occurs. The area of the reservoir experiences a substantial increase,

reaching 17.27 x 1000 m2, while its storage capacity also undergoes growth, reaching 35 m3.

Notably, situated at an altitude of 1850 m above sea level, the reservoir exhibits a vast expanse

spanning 1565 x 1000 m2, accompanied by a noteworthy storage capacity of around 65,989

m3.

Table 3: Reservoir characteristics at dam site R3 (Elevation vs. Area and Volume)

Characteristics of Dam Site R4:

The role of elevation variations at dam site R4 is of great significance in determining

the characteristics of the reservoir, as demonstrated in Table 4 and Figure 10. The

comprehensive records offer a dynamic viewpoint on the reservoir's response to changes in

elevation. Beginning at an elevation of 2080m above sea level, the reservoir does not possess

any surface area or capacity for storing water. Nevertheless, as the altitude gradually increases

to 2085 m, a significant alteration takes place, characterized by the expansion of the reservoir's

surface area to 6.98 x 1000 m2 and an augmented storage capacity of 10 m3. Upon reaching an

elevation of 2200 m above sea level, the reservoir experiences an expansion in its surface area,

reaching a total of 1611 x 1000 m2. This expansion is accompanied by a significant increase in

the reservoir's storage capacity, which now amounts to 67,807 m3. The culmination of this

metamorphosis is witnessed at an altitude of 2275 m above the Earth's sea level, where the

dam site R4 reaches its utmost characteristics a substantial expanse of 7510 x 1000m2 and a

remarkable capacity for storing 358,237 m3.

Figure 10: Correlation between elevation, area, and storage capacity for DAM site R3

The results of this study emphasize the significant impact of changes in elevation on

the physical characteristics of the reservoir, highlighting the crucial significance of this

information in making well-informed decisions regarding the planning and management of

dam site R4.

Figure 11: Correlation between elevation, area, and storage capacity for DAM site R4

Table 4: Reservoir characteristics at dam site R4 (Elevation vs. Area and Volume)

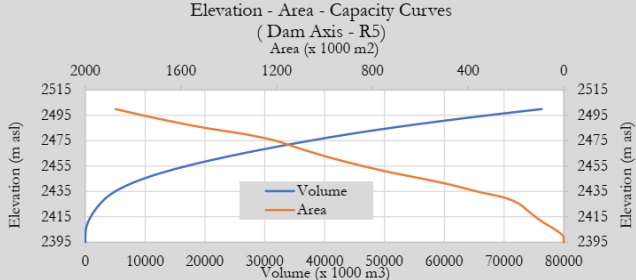

Characteristics of Dam Site R4:

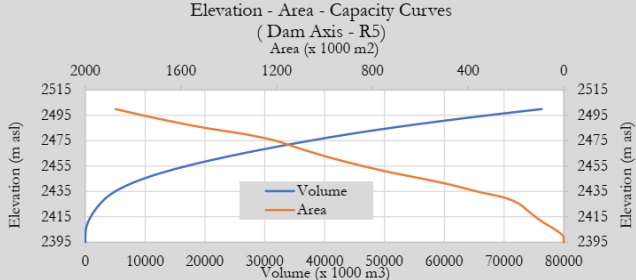

Dam site R5, with an elevation of 2395m above sea level, at first appears to have

neither an area coverage nor a capacity indicated by Figure 11 and Table 5. On the other hand,

significant shifts take place when it reaches its highest elevation of 2500m above sea level. The

storage capacity of the reservoir reaches 76,313 m3, and the area of the reservoir grows to be

1874 x 10000 m2. These data highlight the direct relationship between elevation and the

physical attributes of the reservoir at dam site R5, providing essential insights for the decisions

regarding site planning and management.

Table 5: Reservoir characteristics at dam site R5(Elevation vs. Area and Volume)

Figure 12: Correlation between elevation, area, and storage capacity for DAM site R5

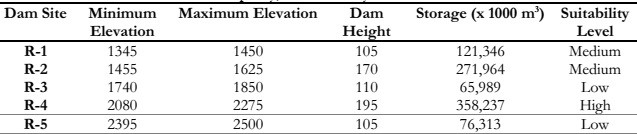

Comparison of Potential Dam Sites:

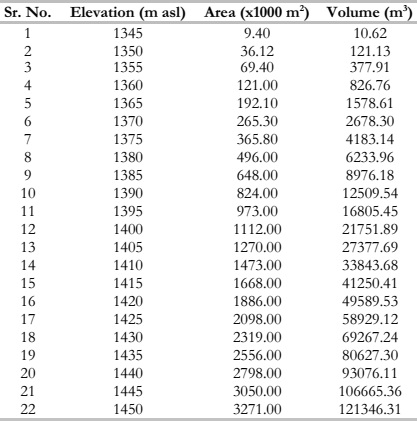

The comparison table (Table 6) offers a detailed assessment of five distinct dam sites

(R-1 through R-5), highlighting their suitability and potential for dam construction. Among

these sites, R-4 stands out as the most promising option. It boasts a wide elevation range from

2080 to 2275 m, resulting in a substantial dam height potential. What sets R-4 apart is its

remarkable storage capacity of 358,237,000 m3, categorizing it as having a "High" suitability

level. This site is exceptionally well-suited for multiple water resource management objectives,

including hydropower generation and flood control, making it the preferred choice among the

options presented. In contrast, the other sites (R-1, R-2, R-3, and R-5) exhibit narrower

elevation ranges and comparatively lower storage capacities, indicating varying degrees of

suitability for specific purposes.

Table 6: Comparison of dam sites (R-1 to R-5) based on elevation, dam Height, storage capacity, and suitability levels

Discussion:

The strategic placement of small dams in the Swat District, Pakistan, as identified in

this study, signifies a pivotal step toward addressing the region's pressing water and energy

challenges. The comprehensive analysis undertaken here melds technical precision, societal

considerations, and environmental consciousness to chart a course for sustainable resource

management. By leveraging advanced technologies such as RS and GIS, and combining these with expert knowledge, we meticulously examined the region's land use, soil profiles, and

precipitation trends.

The foundation of our analysis rested on the adept integration of diverse datasets,

meticulously woven together to create a robust decision-making framework. Through the

application of the priority index statistical method, we identified five distinct locations, each

varying in suitability, for the construction of small dams. Among these, R-1 and R-2 emerged

as sites with medium suitability, holding promise for meeting local water and energy demands

efficiently. R-4, characterized by its high suitability, stands out as a leading candidate for

optimized water resource utilization.

Figure 13: Dam axis profile showing crest level at 1625 m ASL.

The significance of these findings is underscored by the visual representation provided

in Figure 6, which serves as a guiding map for efficient water management in the region. This

map, highlighting top locations for small dam construction, offers clear directives for future

endeavors in water resource management. Looking forward, the implementation of these

identified sites bears the potential to usher in a new era for the Swat District. Through the

amalgamation of engineering expertise, active community involvement, and ecological

sensitivity, these small dams are poised not only to fulfill their immediate purpose but also to

foster regional growth and resilience. By empowering local communities and promoting

sustainable change, the construction of small dams in Pakistan's Swat District emerges as a

catalyst for transformative progress.

In light of these results, it is imperative for government bodies and policymakers to

heed the insights provided by this study. The identified sites offer a tangible course of action,

balancing the necessities of water and energy demands with the inherent opportunities present

in the region. The successful realization of these small dams hinges not only on their

construction but also on the ongoing commitment to ecological preservation and community

engagement. Therefore, it is recommended that future initiatives prioritize these aspects,

ensuring that the potential benefits of these small dams are maximized for the betterment of

the Swat District and its inhabitants.

Conclusion

The strategic placement of small dams offers a glimmer of hope for our region to meet

the evolving demands of our water and energy systems as we stand at the crossroads of

escalating water and energy challenges. The beautiful landscape of Swat District, Pakistan is

ripe with potential sites for multi-purpose small dams, and this study has been instrumental in

charting the course, identifying, and assessing those sites. We take a comprehensive view of

resource management by carefully balancing technical requirements, societal and economic

factors, and a firm dedication to protecting the natural world. The wise application of a diverse array of data sources formed the basis of our decision-making process. To decipher the

complexities of the Swat District's land use and land cover map, soil profiles, and precipitation

trends, we employed cutting-edge technology and expert knowledge. These masterfully woven

datasets were the bedrock upon which we based our site selection voyage. We used the

precision of a statistical method called the priority index to guide the use of RS and GIS

technologies to uncover these promising locations. Because of this method, water resource

managers and decision-makers now have a detailed suitability map at their disposal. Based on

the outcomes of this exhaustive assessment, five distinct geographical sites displaying diverse

levels of suitability have surfaced. Notably, locations R-1 and R-2 exhibit a moderate level of

appropriateness, suggesting their potential efficacy in satisfying local water and energy

requisites. Due to its high suitability, R-4 is a leading candidate for efficient use of water

resources. Low suitability, on the other hand, creates opportunities that strike a fine balance

between protecting the environment and making the most of the resources at hand in regions

R-3 and R-5.

Figure 6 map serves as a visual record of our efforts that highlights the top and

topnotch locations to build small dams, providing clear instructions for efficient water

management. Concluding our research, these five small dams, characterized by their individual

suitability profiles, hold the promise of efficiently mitigating the water and energy challenges

confronting the Swat District. The future is bright, thanks to engineering prowess, community

participation, and ecological sensitivity, and it will guarantee that these small dams not only

serve their immediate purpose but also contribute to the growth and resilience of the region.

Building small dams in Pakistan's Swat District is central to empowering local communities

and facilitating change. The findings of the study illuminate the path forward for government

officials and policymakers, providing a roadmap that strikes a balance between essential

requirements and available opportunities.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All authors have read, understood, and have complied as applicable with

the statement on "Ethical responsibilities of Authors" as found in the Instructions for Authors

and are aware that with minor exceptions, no changes can be made to authorship once the

paper is submitted

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

Reference

[1] T. Kumar and D. Jhariya, “Identification of Rainwater Harvesting Sites using SCS-CN

Methodology, Remote Sensing and Geographical Information System Techniques,”

Geocarto Int., vol. 32, pp. 1–43, 2016, doi: 10.1080/10106049.2016.1213772.

[2] R. Agarwal, P. Garg, and R. Garg, “Remote Sensing and GIS Based Approach for

Identification of Artificial Recharge Sites,” Water Resour. Manag., vol. 27, 2013, doi:

10.1007/s11269-013-0310-7.

[3] J. Krois and A. Schulte, “GIS-based multi-criteria evaluation to identify potential sites

for soil and water conservation techniques in the Ronquillo watershed, northern Peru,”

Appl. Geogr., vol. 51, pp. 131–142, 2014, doi:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.04.006.

[4] E. Blanc and E. Strobl, “Is Small Better? A Comparison of the Effect of Large and

Small Dams on Cropland Productivity in South Africa,” World Bank Econ. Rev., vol.

28, no. 3, pp. 545–576, 2014, doi: 10.1093/wber/lht026.

[5] G. Mugo and P. Odera, “Site selection for rainwater harvesting structures in Kiambu

County-Kenya,” Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Sp. Sci., vol. 22, pp. 155–164, 2019, doi:

10.1016/j.ejrs.2018.05.003.

[6] K. Balkhair and K. Rahman, “Development and assessment of rainwater harvesting suitability map using Analytical Hierarchy Process, GIS, and RS techniques,” Geocarto

Int., vol. 36, pp. 1–19, 2019, doi: 10.1080/10106049.2019.1608591.

[7] A. Adham, M. Riksen, R. Abed, S. Shadeed, and C. Ritsema, “Assessing Suitable

Techniques for Rainwater Harvesting Using Analytical Hierarchy Process ( AHP )

Methods and GIS Techniques,” 2022.

[8] D. Khan, A. Raziq, H. V. Young, T. Sardar, and Y. Liou, “Identifying Potential Sites

for Rainwater Harvesting Structures in Ghazi Tehsil , Khyber Pakhtunkhwa , Pakistan

, Using,” 2022.

[9] A. Hussain, “Investigating feasible sites for multi _ purpose small dams in Swat District

of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province , Pakistan : socioeconomic and environmental

considerations,” pp. 10852–10875, 2022, doi: 10.1007/s10668-021-01886-z.

[10] M. Kumar, A. Agarwal, and R. Bali, “Delineation of potential sites for water harvesting

structures using remote sensing and GIS,” J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens., vol. 36, pp.

323–334, 2008, doi: 10.1007/s12524-008-0033-z.

[11] T. Naseef and R. Thomas, “Identification of Suitable Sites for Water Harvesting

Structures in Kecheri River Basin,” Procedia Technol., vol. 24, pp. 7–14, 2016, doi:

10.1016/j.protcy.2016.05.003.

[12] S. Mahmoud and P. Alazba, “The potential of in situ rainwater harvesting in arid

regions: developing a methodology to identify suitable areas using GIS-based decision

support system,” Arab. J. Geosci., 2014, doi: 10.1007/s12517-014-1535-3.

[13] S. H. Mahmoud and A. A. Alazba, “The potential of in situ rainwater harvesting in arid

regions: developing a methodology to identify suitable areas using GIS-based decision

support system,” Arab. J. Geosci., vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 5167–5179, 2015, doi:

10.1007/s12517-014-1535-3.

[14] A. Adham et al., “International Soil and Water Conservation Research A GIS-based

approach for identifying potential sites for harvesting rainwater in the Western Desert

of Iraq,” Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res., vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 297–304, 2018, doi:

10.1016/j.iswcr.2018.07.003.

[15] S. H. M. X. Tang, “Monitoring prospective sites for rainwater harvesting and

stormwater management in the United Kingdom using a GIS-based decision support

system,” Environ. Earth Sci., pp. 8621–8638, 2015, doi: 10.1007/s12665-015-4026-2.

[16] A. Ochir, D. Boldbaatar, M. Zorigt, T. Solongo, and J. van Genderen, “Site selection

for water harvesting ponds using spatial multi criteria analysis in a region with

fluctuating climate,” Geocarto Int., vol. 33, pp. 1–33, 2017, doi:

10.1080/10106049.2017.1289563.

[17] M. Shahid, K. Rahman, K. Balkhair, and D. Nabi, “Impact assessment of land use and

climate changes on the variation of runoff in Margalla Hills watersheds, Pakistan,”

Arab. J. Geosci., vol. 13, 2020, doi: 10.1007/s12517-020-5231-1.

[18] K. Kochhar et al., “Is the Glass Half Empty or Half Full ? Issues in Managing Water

Challenges and Policy Instruments,” 2015.

[19] A. Hussain et al., “Observed trends and variability of seasonal and annual precipitation

in Pakistan during 1960–2016,” Int. J. Climatol., 2022, doi: 10.1002/joc.7709.

[20] M. Shahid and K. U. Rahman, “Identifying the Annual and Seasonal Trends of

Hydrological and Climatic Variables in the Indus Basin Pakistan,” Asia-Pacific J.

Atmos. Sci., vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 191–205, 2021, doi: 10.1007/s13143-020-00194-2.

[21] S. Bangash, “Socio-Economic Conditions of Post-Conflict Swat: A Critical Appraisal,”

Tigah A J. Peace Dev., vol. 2, no. December, pp. 66–79, 2012.

[22] Atta-ur-Rahman and A. N. Khan, “Analysis of flood causes and associated socioeconomic damages in the Hindukush region,” Nat. Hazards, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 1239– 1260, Dec. 2011, doi: 10.1007/S11069-011-9830-8/METRICS.

[23] M. Qasim, K. Hubacek, M. Termansen, and L. Fleskens, “Modelling land use change

across elevation gradients in district Swat, Pakistan,” Reg. Environ. Chang., vol. 13, no.

3, pp. 567–581, 2013, doi: 10.1007/s10113-012-0395-1.

[24] A. Zamani, A. Sharifi, S. Felegari, A. Tariq, and N. Zhao, “Agro Climatic Zoning of

Saffron Culture in Miyaneh City by Using WLC Method and Remote Sensing Data,”

Agric. 2022, Vol. 12, Page 118, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 118, Jan. 2022, doi:

10.3390/AGRICULTURE12010118.

[25] A. S. A.-A. S. A.-H. M. A.-E. M. A.-A. Tariq, “Agricultural Field Extraction with Deep

Learning Algorithm and Satellite Imagery,” J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens., vol. v. 50, no.

2, pp. 417-423–2022 v.50 no.2, 2022, doi: 10.1007/s12524-021-01475-7.

[26] H. Waqas et al., “Flash Flood Susceptibility Assessment and Zonation Using an

Integrating Analytic Hierarchy Process and Frequency Ratio Model for the Chitral

District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan,” Water 2021, Vol. 13, Page 1650, vol. 13, no.

12, p. 1650, Jun. 2021, doi: 10.3390/W13121650.

[27] F. Islam et al., “Landslide susceptibility mapping (LSM) of Swat District, Hindu Kush

Himalayan region of Pakistan, using GIS-based bivariate modeling,” Front. Environ.

Sci., vol. 10, no. October, pp. 1–18, 2022, doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.1027423.

[28] Z. H. Dahri, B. Ahmad, J. H. Leach, and S. Ahmad, “Satellite-based snowcover

distribution and associated snowmelt runoff modeling in Swat River Basin of Pakistan,”

Proc. Pakistan Acad. Sci., vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 19–32, 2011.

[29] F. Bazzani, “Atlas of the Natural Resources Evaluation in Swat Valley , Khyber

Pakhtunkhwa , Islamic Republic of Pakistan,” no. May, 2013.

[30] S. R. Khan and S. R. Khan, “Assessing poverty-deforestation links: Evidence from

Swat, Pakistan,” Ecol. Econ., vol. 68, no. 10, pp. 2607–2618, 2009, doi:

10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.04.018.

[31] M. S. Bacha, M. Muhammad, Z. Kılıç, and M. Nafees, “The dynamics of public

perceptions and climate change in swat valley, khyber pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan,”

Sustain., vol. 13, no. 8, pp. 1–22, 2021, doi: 10.3390/su13084464.

[32] A. Sajjad et al., “Application of Remote Sensing and GIS in Forest Cover Change in

Tehsil Barawal, District Dir, Pakistan,” Am. J. Plant Sci., vol. 06, no. 09, pp. 1501–1508,

2015, doi: 10.4236/ajps.2015.69149.

[33] T. Adugna, W. Xu, and J. Fan, “Comparison of Random Forest and Support Vector

Machine Classifiers for Regional Land Cover Mapping Using Coarse Resolution FY-

3C Images,” Remote Sens., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 1–22, 2022, doi: 10.3390/rs14030574.

[34] K. S. Balkhair and K. Ur Rahman, “Development and assessment of rainwater

harvesting suitability map using analytical hierarchy process, GIS and RS techniques,”

Geocarto Int., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 421–448, 2021, doi: 10.1080/10106049.2019.1608591.

[35] Z. K. Motlagh, A. Lotfi, S. Pourmanafi, S. Ahmadizadeh, and A. Soffianian, “Spatial

modeling of land-use change in a rapidly urbanizing landscape in central Iran:

integration of remote sensing, CA-Markov, and landscape metrics,” Environ. Monit.

Assess., vol. 192, no. 11, 2020, doi: 10.1007/s10661-020-08647-x.

[36] B. R. Parida and S. P. Mandal, “Polarimetric decomposition methods for LULC

mapping using ALOS L-band PolSAR data in Western parts of Mizoram, Northeast

India,” SN Appl. Sci., vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 1–15, 2020, doi: 10.1007/s42452-020-2866-1.