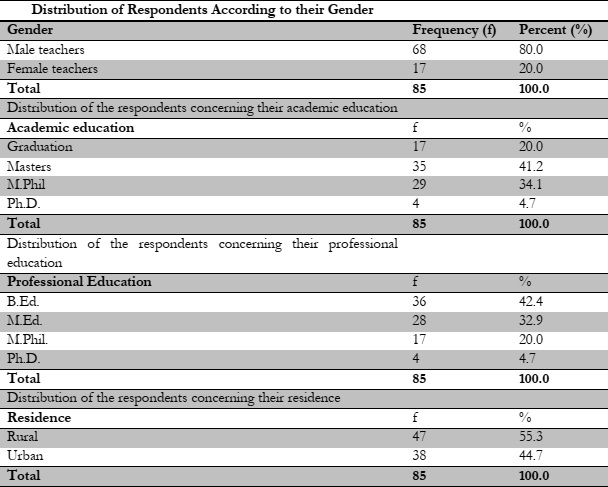

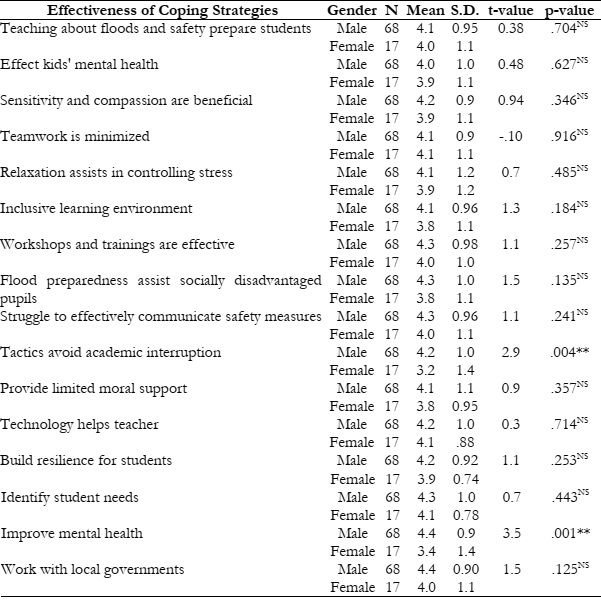

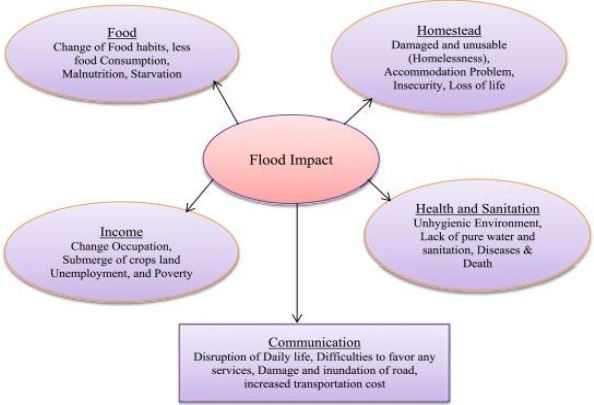

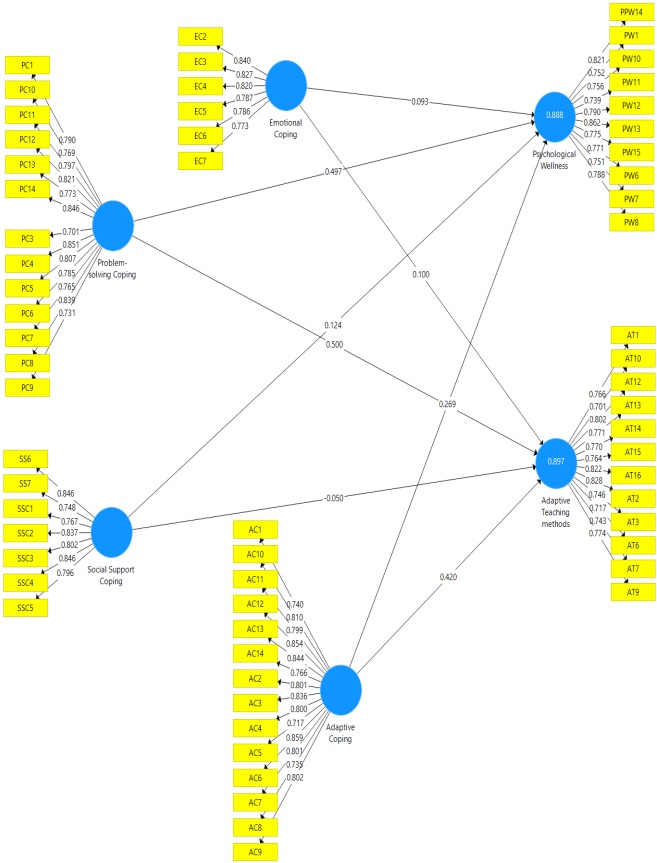

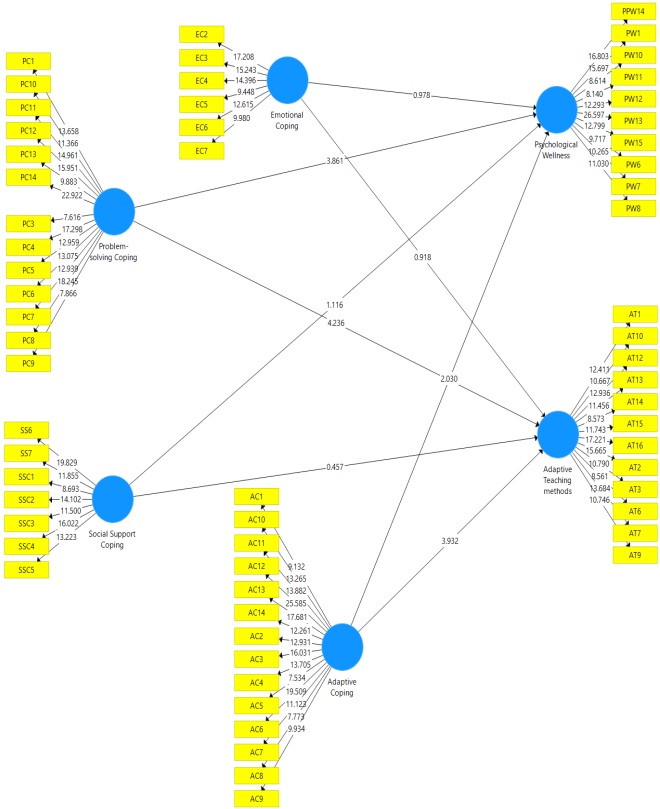

The findings of this study shed light on the coping strategies employed by teachers in Taunsa Sharif, Punjab, Pakistan, and their impact on well-being in the context of flood-prone areas. The study underscores the significance of exploring coping strategies as integral components of teacher wellbeing and community resilience. Proposed research reveals a positive association between active coping approaches and teacher's psychological well-being. Effective coping strategies were found to be linked to lower psychological distress and matched with Govt of Pakistan statistics [19]. Teachers in Taunsa Sharif appeared to be aware of the value of employing diverse coping strategies, reflecting the need for both awareness and resources in managing the unique challenges presented by flood-prone regions. This aligns with existing literature emphasizing the crucial role of coping mechanisms in mitigating the psychological impact of disasters [20]. Our findings are consistent with previous research that highlights the positive impact of active coping strategies on well-being [21]. An interesting aspect of our study is the variation in coping strategy adoption among different school levels. While primary and secondary school teachers predominantly utilized certain coping strategies, teachers at higher levels as their primary approaches, results are at par with Halder [22]. This variation may reflect the differing demands and responsibilities of teachers at various educational levels as Zwęgliński has discussed the same [23]. Policymakers and education authorities must recognize these differences and provide tailored support and training to address the unique needs of teachers at different levels as also revealed the same by Khalid [24].

One significant finding is the pivotal role of collaborative efforts and community engagement in flood management. Teachers in Taunsa Sharif actively participated in community-based flood response and resilience-building initiatives. This underscores the importance of community involvement in disaster management as shown in the same findings by [25]. Teachers, as trusted figures within the community, play a vital role in fostering a sense of preparedness and resilience. The study identified specific training needs, with the most prominent being motivational training and cultural sensitivity. These findings emphasize the importance of professional development programs that address these specific needs. While this research provides a foundation for understanding training needs, future efforts should focus on developing and implementing training programs tailored to these needs and evaluating their effectiveness as depicted by Khan [26]. The ranking of training needs for teachers in flood-prone areas provides valuable insights into the specific requirements for building resilience and enhancing disaster preparedness within the education sector as similar results found by Kumar [27]. These training needs are of paramount importance in addressing the unique challenges faced by educators in such regions. The top-ranked training need, "Motivational," underscores the critical role of maintaining motivation among teachers Smith revealed that the role of motivation traits in decision-making depends on continuous training [28]. In flood-prone regions, educators often face overwhelming challenges, from disrupted classrooms to students dealing with upset. Sustaining motivation is essential for teachers to navigate these challenging circumstances effectively, same statistics written by smith in his book Teachers as Role Models [29]. Motivated teachers can inspire their students, fostering a positive and resilient learning environment [30]. This training highlights the need for strategies that empower teachers to stay motivated and inspire resilience within themselves and their students. Culturally Sensitive" training is prioritized, emphasizing the importance of educators understanding and respecting the diverse cultural backgrounds of their communities. In flood-prone regions, communities often have distinct cultural norms and practices. Teachers need to adapt their coping strategies to resonate with local contexts. Cultural sensitivity not only enhances their effectiveness but also fosters trust and community integration, which is vital in disaster response and resilience building [31]. This training need recognizes the need for teachers to be culturally competent in addressing the specific needs and perspectives of their students and their communities. The third-ranked training need, "Working with Active Citizen Formation Groups," highlights the significance of collaboration between teachers and local communities as Brown discussed that direct and moderating impacts of the CARE mindfulness-based professional learning program for teachers on childrens academic and social-emotional outcomes [32]. Teachers play a central role in community-based disaster response and resilience-building efforts. Active engagement with citizen formation groups can facilitate effective disaster management, as local communities often possess valuable knowledge and resources. This training need emphasizes the importance of equipping teachers with the skills and knowledge to collaborate with local groups effectively. It also underscores the importance of involving teachers in community-driven initiatives for enhanced disaster resilience. These distinctions in training needs underscore the practical and contextual challenges faced by teachers in flood-prone areas [16]. They highlight the necessity for tailored teacher training and professional development programs that address the specific requirements of these educators. Such programs should equip teachers with the necessary skills and knowledge for effective disaster response, resilience building, and community collaboration. Furthermore, considering the ranking of training needs, it becomes apparent that teachers in flood-prone areas face unique challenges and demands. These distinctions highlight the necessity to investigate gender-specific preferences in coping strategies, emphasizing potential areas for further exploration [33]. Customized professional development programs tailored to the needs of teachers, both male and female, are essential for bolstering disaster resilience within educational settings [34]. These programs can help teachers effectively address the challenges posed by their environment and contribute to building a more resilient educational system in flood-prone regions [35].

The study exhibits several inherent limitations that deserve acknowledgment. Firstly, it is imperative to recognize that the assessment is confined exclusively to the distinct geographical context of Taunsa Sharif within Punjab, Pakistan. Consequently, the coping strategies identified may not be universally representative of those employed in other regions prone to flooding. Secondly, the identification of training needs is fundamentally grounded in the perceptions of teachers in Taunsa Sharif, rendering the applicability of these findings to teachers in analogous regions less direct. Thirdly, the studys evaluation primarily centers on the perspectives of teachers, potentially offering a somewhat narrower view of the overall impact on students and their families. Furthermore, the exploration of these perceptions is inherently delimited to the specific milieu of Taunsa Sharif, potentially omitting the full spectrum of perspectives prevalent in other flood-prone regions. Lastly, while the study indicates the potential for developing training programs, its essential to recognize that further customization may be requisite to align with the distinctive characteristics and needs of other flood-prone areas within the broader Punjab region.

[1] C. S. Abacioglu, M. VolmanandA. H. Fischer, “Teachers multicultural attitudes and perspective taking abilities as factors in culturally responsive teaching,” Br. J. Educ. Psychol., vol. 90, no. 3, pp. 736–752, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.1111/BJEP.12328.

[2] M. J. Adams, “Marital Status Demographics and Decision-Making Strategies,” J. Consum. Behav., vol. 16, pp. 432–447, 2019.

[3] D. Ahmad and M. Afzal, “Flood hazards and livelihood vulnerability of flood-prone farm-dependent Bait households in Punjab, Pakistan,” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., vol. 29, no. 8, pp. 11553–11573, Feb. 2022, doi: 10.1007/S11356-021-16443-4/METRICS.

[4] D. Ahmad, M. AfzalandA. Rauf, “Flood hazards adaptation strategies: a gender-based disaggregated analysis of farm-dependent Bait community in Punjab, Pakistan,” Environ. Dev. Sustain., vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 865–886, Jan. 2021, doi: 10.1007/S10668-020-00612-5/METRICS.

[5] A. H. Ahmad, T., S. Malik, “Data-driven and culturally attuned approaches in disaster management: a study of cross-cultural awareness training for educators,” Int. J. Disaster Stud., vol. 15, pp. 78–93, 2021.

[6] M. A. S. Ahmar, A. S., Khan, M. S., “The Role of Teamwork in Disaster Management: A Case Study of Floods in Pakistan,” J. Disaster Response Collab., vol. 6, pp. 112–125, 2019.

[7] T. Mai et al., “Defining flood risk management strategies: A systems approach,” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., vol. 47, p. 101550, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1016/J.IJDRR.2020.101550.

[8] C. Clar, L. Junger, R. NordbeckandT. Thaler, “The impact of demographic developments on flood risk management systems in rural regions in the Alpine Arc,” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., vol. 90, p. 103648, May 2023, doi: 10.1016/J.IJDRR.2023.103648.

[9] R. M. J. Chen, L., J..P. Williams, “Exploring Educational Background Diversity in Research Samples,” J. Soc. Sci. Res., vol. 45, pp. 215–230, 2020.

[10] S. Hasbi, Z. HanimandS. Bin Husain, “The implementation optimization of school development plan in flood disaster mitigation policy in tropical rainforest (Case study at state junior high school 5 Samarinda),” Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 100440, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1016/J.SSAHO.2023.100440.

[11] S. Vanwoerden, J. Chandler, K. Cano, P. Mehta, P. A. PilkonisandC. Sharp, “Sampling Methods in Personality Pathology Research: Some Data and Recommendations,” Personal. Disord. Theory, Res. Treat., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 19–28, 2023, doi: 10.1037/PER0000593.

[12] A. M. J. Davis, C. J., “Socio-Economic Traits and Decision-Making Approaches,” J. Manag. Organ. Stud., vol. 14, pp. 76–93, 2021.

[13] “A rapid geospatial flood impact assessment in Pakistan, 2022,” A rapid geospatial flood impact Assess. Pakistan, 2022, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.4060/CC2873EN.

[14] H. Kawasaki, S. Yamasaki, M. YamakidoandY. Murata, “Introductory Disaster Training for Aspiring Teachers: A Pilot Study,” Sustain. 2022, Vol. 14, Page 3492, vol. 14, no. 6, p. 3492, Mar. 2022, doi: 10.3390/SU14063492.

[15] M. R. Brands et al., “Patients and health care providers perspectives on quality of hemophilia care in the Netherlands: a questionnaire and interview study,” Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost., vol. 7, no. 4, p. 100159, May 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.rpth.2023.100159.

[16] B. Hossain, M. S. SohelandC. M. Ryakitimbo, “Climate change induced extreme flood disaster in Bangladesh: Implications on peoples livelihoods in the Char Village and their coping mechanisms,” Prog. Disaster Sci., vol. 6, p. 100079, Apr. 2020, doi: 10.1016/J.PDISAS.2020.100079.

[17] E. M. Waltner, W. RießandC. Mischo, “Development and Validation of an Instrument for Measuring Student Sustainability Competencies,” Sustain. 2019, Vol. 11, Page 1717, vol. 11, no. 6, p. 1717, Mar. 2019, doi: 10.3390/SU11061717.

[18] C. Biswas, S. K. Deb, A. A. T. HasanandM. S. A. Khandakar, “Mediating effect of tourists emotional involvement on the relationship between destination attributes and tourist satisfaction,” J. Hosp. Tour. Insights, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 490–510, 2020, doi: 10.1108/JHTI-05-2020-0075/FULL/XML.

[19] “Pakistan Floods 2022: Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) | United Nations Development Programme.” Accessed: Nov. 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.undp.org/pakistan/publications/pakistan-floods-2022-post-disaster-needs-assessment-pdna

[20] K. A. K. C. K. Gupta, “New ideas for trans-boundary early warning system in Asia. Transboundary Early Warning Systems in Asia,” vol. 9, pp. 180–189, 2019.

[21] A. R. Hamidi, J. Wang, S. GuoandZ. Zeng, “Flood vulnerability assessment using MOVE framework: a case study of the northern part of district Peshawar, Pakistan,” Nat. Hazards, vol. 101, no. 2, pp. 385–408, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1007/S11069-020-03878-0/METRICS.

[22] B. Halder et al., “Large-Scale Flood Hazard Monitoring and Impact Assessment on Landscape: Representative Case Study in India,” Sustain. 2023, Vol. 15, Page 11413, vol. 15, no. 14, p. 11413, Jul. 2023, doi: 10.3390/SU151411413.

[23] T. Zwęgliński, C. J. Vermeulen, M. Smolarkiewicz, A. F. Ryznar, K. BralewskaandB. Wiśniewski, “DYNAMIC FLOOD MODELLING IN DISASTER RESPONSE,” Innov. Cris. Manag., pp. 173–197, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.4324/9781003256977-14/DYNAMIC-FLOOD-MODELLING-DISASTER-RESPONSE-TOMASZ-ZW.

[24] N. Khalid, “Teachers perception regarding English as a subject at elementary level in district Nankana Sahib. M.Phil. Education Thesis, Institute of Agri. Ext., Education and Rural Development, Faculty of Social Sciences, Univ. of Agri., Faisalabad.,” 2022.

[25] D. J. Moisès, N. KgabiandO. Kunguma, “Integrating Top-Down and Community-Centric Approaches for Community-Based Flood Early Warning Systems in Namibia,” Challenges 2023, Vol. 14, Page 44, vol. 14, no. 4, p. 44, Oct. 2023, doi: 10.3390/CHALLE14040044.

[26] F. A. and S. A. Khan, N., “Emotional Support and Critical Decision-Making: A Crossroads of Guidance and Disaster Preparedness Among Educators,” J. Disaster Educ. Train., vol. 18, no. 65–78, 2022.

[27] S. H. L. Kumar, S., J.A. Martinez, “Early-Career Educators: Shaping Perspectives in Modern Education,” Emerg. Pedagog. Trends, vol. 28, pp. 78–92, 2020.

[28] E. F. W. Smith, A.B., C.D. Johnson, “The role of demographic traits in decision-making,” J. Behav. Stud., vol. 15, pp. 45–62, 2019.

[29] M. W. J. Smith, E. A., “Higher Education Attainment in Participant Samples: A Comparative Study,” Educ. Stud. Journal., vol. 36, pp. 511–525, 2022.

[30] C. Azorín, A. HarrisandM. Jones, “Taking a distributed perspective on leading professional learning networks,” Sch. Leadersh. Manag., vol. 40, no. 2–3, pp. 111–127, May 2020, doi: 10.1080/13632434.2019.1647418.

[31] B. Kohn, T., & Medina, “Disaster Resilience in Education: The Challenge of Motivating and Preparing Teachers for the Unexpected,” Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ., vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 573–586, 2019.

[32] J. L. Brown et al., “Direct and Moderating Impacts of the CARE Mindfulness-Based Professional Learning Program for Teachers on Childrens Academic and Social-Emotional Outcomes”, doi: 10.31234/OSF.IO/2AFYS.

[33] K. F. Dintwa, G. LetamoandK. Navaneetham, “Vulnerability perception, quality of lifeandindigenous knowledge: A qualitative study of the population of Ngamiland West District, Botswana,” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., vol. 70, p. 102788, Feb. 2022, doi: 10.1016/J.IJDRR.2022.102788.

[34] C. Qing, S. Guo, X. DengandD. Xu, “Farmers disaster preparedness and quality of life in earthquake-prone areas: The mediating role of risk perception,” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., vol. 59, p. 102252, Jun. 2021, doi: 10.1016/J.IJDRR.2021.102252.

[35] J. F. Hair, J. J. Risher, M. SarstedtandC. M. Ringle, “When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM,” Eur. Bus. Rev., vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 2–24, Jan. 2019, doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203/FULL/XML.