Monitoring of Cortisol Levels in Hog Deer with Varying Environment Exposure

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.33411/ijist/2022040321Keywords:

Captive Environment, Glucocorticoids, Cortisol; Stress levels, Hog deerAbstract

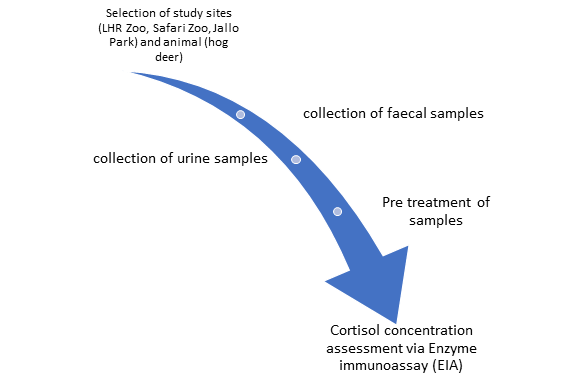

Hog deer (Axis porcinus) is one of the least studied animal species in Pakistan. It belongs to Order Artiodactyla and the family Cervidae. IUCN classified Axis porcinus as an endangered species in 2008. The present study was conducted to investigate the effects of varying environmental exposure, genders, and seasonal changes on captive hog deer (A. porcinus) at Lahore Zoo, Safari Zoo, and Jallo Park in Lahore, Pakistan. Non-invasive techniques were used to monitor stress levels in hog deer. For sample collection, four definite months belonging to two seasons’ winter and summer were considered. A total of 48 urine and faecal samples were collected from both male and female hog deer. Seasonal fluctuations have been found to have a significant impact on faecal and urinary cortisol levels. Higher cortisol levels were found in both male and female hog deer in the summer season at all three visited sites. Fluctuations in environmental exposure at three research sites had a significant impact on faecal and urinary cortisol levels. Higher levels of cortisol were found in both male and female hog deer at Jallo park and Lahore Zoo, as compared to Safari Zoo. It was concluded that lower cortisol levels at Safari Zoo might be due to better environmental conditions and more flexible enclosure size and interaction of various species of deer. Temperature affected hog deer cortisol levels in summer, as higher levels were measured in summer compared to winter. In addition, sex did not predict any stress levels in hog deer. It has been suggested that a large enclosure size can control levels of cortisol in hog deer.

References

I. J. Biosci et al., “Comparative study of endo-parasites in captive hog deer (Axis Porcinus),” 2015, Accessed: Aug. 27, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://130.203.136.95/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.674.3553

T. J. (Tom J. . Roberts, “The mammals of Pakistan,” p. 525, 1997, Accessed: Aug. 27, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.goodreads.com/work/best_book/3524440-the-mammals-of-pakistan

A. Sinha, B. P. Lahkar, and S. A. Hussain, “Current population status of the endangered Hog Deer Axis porcinus (Mammalia: Cetartiodactyla: Cervidae) in the Terai grasslands: A study following political unrest in Manas National Park, India,” J. Threat. Taxa, vol. 11, no. 13, pp. 14655–14662, 2019, doi: 10.11609/JOTT.5037.11.13.14655-14662.

M. Arshad, I. Ullah, M. Jamshed, I. Chaudhry, N. Ul, and H. Khan, “Estimating Hog deer Axis porcinus population in the riverine forest of Taunsa Barrage Wildlife Sanctuary , Punjab , Pakistan,” Pak. J. Zool., vol. 28, no. 451, pp. 25–28, 2012.

S. Kanungo, a Das, and D. G. M, “Prevalence of gastro-intestinal helminthiasis in captive deer of Bangladesh,” Vet. Res., no. 1288421279, pp. 42–45, 2012.

S. Brook, “Indochinese hog deer Axis porcinus annamiticus on the brink of extinction Articles Possible occurrence of Muntiacus gongshanensis in Dibang Valley district of Arunachal Pradesh , Northeast India by Ambika Aiyadurai and Indochinese Hog Deer Axis porcinus a,” no. April 2015, 2016.

J. C. Wingfield and R. M. Sapolsky, “Reproduction and resistance to stress: When and how,” J. Neuroendocrinol., vol. 15, no. 8, pp. 711–724, Aug. 2003, doi: 10.1046/J.1365-2826.2003.01033.X.

G. Davey, “Visitor behavior in zoos: A review,” Anthrozoos, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 143–157, 2006, doi: 10.2752/089279306785593838.

E. A. Young and N. Breslau, “Saliva cortisol in posttraumatic stress disorder: A community epidemiologic study,” Biol. Psychiatry, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 205–209, Aug. 2004, doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.05.011.

and M. H. Hodges, K., J. Brown, Noninvasive monitoring of reproductive status and stress. 2010.

B. H. Natelson, J. E. Ottenweller, J. A. Cook, D. Pitman, R. McCarty, and W. N. Tapp, “Effect of stressor intensity on habituation of the adrenocortical stress response,” Physiol. Behav., vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 41–46, 1988, doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(88)90096-0.

C. Lutz, A. Well, and M. Novak, “Stereotypic and self-injurious behavior in rhesus macaques: A survey and retrospective analysis of environment and early experience,” Am. J. Primatol., vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 1–15, May 2003, doi: 10.1002/AJP.10075.

N. Silanikove and D. N. Koluman, “Impact of climate change on the dairy industry in temperate zones: Predications on the overall negative impact and on the positive role of dairy goats in adaptation to earth warming,” Small Rumin. Res., vol. 123, no. 1, pp. 27–34, Jan. 2015, doi: 10.1016/J.SMALLRUMRES.2014.11.005.

S. K. Wasser, S. L. Monfort, and D. E. Wildt, “Rapid extraction of faecal steroids for measuring reproductive cyclicity and early pregnancy in free-ranging yellow baboons (Papio cynocephalus cynocephalus),” J. Reprod. Fertil., vol. 92, no. 2, pp. 415–423, 1991, doi: 10.1530/JRF.0.0920415.

G. Mason, R. Clubb, N. Latham, and S. Vickery, “Why and how should we use environmental enrichment to tackle stereotypic behaviour?,” Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., vol. 102, no. 3–4, pp. 163–188, Feb. 2007, doi: 10.1016/J.APPLANIM.2006.05.041.

K. Carlstead, J. Seidensticker, and R. Baldwin, “Environmental enrichment for zoo bears,” Zoo Biol., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 3–16, Jan. 1991, doi: 10.1002/ZOO.1430100103.

R. A. Kastelein and P. R. Wiepkema, “A digging trough as occupational therapy for Pacific Walruses (Odobenus rosmarus divergens) in human care,” Aquat. Mamm., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 9–17, 1989, [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ronald_Kastelein/publication/40213359_A_digging_trough_as_occupational_therapy_for_Pacific_Walruses_Odobenus_rosmarus_divergens_in_human_care/links/00b4952b480cd113cd000000.pdf

S. Huber, R. Palme, and W. Arnold, “Effects of season, sex, and sample collection on concentrations of fecal cortisol metabolites in red deer (Cervus elaphus),” Gen. Comp. Endocrinol., vol. 130, no. 1, pp. 48–54, Jan. 2003, doi: 10.1016/S0016-6480(02)00535-X.

G. A. Bubenik, D. Schams, R. G. White, J. Rowell, J. Blake, and L. Bartos, “Seasonal levels of metabolic hormones and substrates in male and female reindeer (Rangifer tarandus),” Comp. Biochem. Physiol. - C Pharmacol. Toxicol. Endocrinol., vol. 120, no. 2, pp. 307–315, 1998, doi: 10.1016/S0742-8413(98)10010-5.

J. R. Ingram, J. N. Crockford, and L. R. Matthews, “Ultradian, circadian and seasonal rhythms in cortisol secretion and adrenal responsiveness to ACTH and yarding in unrestrained red deer (Cervus elaphus) stags,” J. Endocrinol., vol. 162, no. 2, pp. 289–300, 1999, doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1620289.

T. Fehér, Z. Zomborszky, and E. Sándor, “Dehydroepiandrosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate, and their relation to cortisol in red deer (Cervus elaphus),” Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Comp., vol. 109, no. 3, pp. 247–252, 1994, doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(94)00065-I.

B. R. Brinklow and J. M. Forbes, “Effect of pinealectomy on the plasma concentrations of prolactin, cortisol and testosterone in sheep in short and skeleton long photoperiods,” J. Endocrinol., vol. 100, no. 3, pp. 287–294, 1984, doi: 10.1677/JOE.0.1000287.

S. Dikmen and P. J. Hansen, “Is the temperature-humidity index the best indicator of heat stress in lactating dairy cows in a subtropical environment?,” J. Dairy Sci., vol. 92, no. 1, pp. 109–116, 2009, doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1370.

G. J. Mason, “Species differences in responses to captivity: stress, welfare and the comparative method,” Trends Ecol. Evol., vol. 25, no. 12, pp. 713–721, Dec. 2010, doi: 10.1016/J.TREE.2010.08.011.

B. Allwin et al., “Assessment of Faecal Cortisol Levels in Free-Ranging Nilgiri Tahrs (Nilgiritragus hylocrius) in Correlation with Meteorological Parameters: A Non-Invasive Study,” J. Climatol. Weather Forecast., vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 1–4, 2016, doi: 10.4172/2332-2594.1000175.

J. J. Millspaugh and B. E. Washburn, “Use of fecal glucocorticoid metabolite measures in conservation biology research: Considerations for application and interpretation,” Gen. Comp. Endocrinol., vol. 138, no. 3, pp. 189–199, 2004, doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.07.002.

D. Saltz and G. C. White, “Urinary Cortisol and Urea Nitrogen Responses to Winter Stress in Mule Deer,” J. Wildl. Manage., vol. 55, no. 1, p. 1, 1991, doi: 10.2307/3809235.

W. Goymann, “Noninvasive monitoring of hormones in bird droppings: Physiological validation, sampling, extraction, sex differences, and the influence of diet on hormone metabolite levels,” Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., vol. 1046, pp. 35–53, 2005, doi: 10.1196/ANNALS.1343.005.

J. C. Beehner and T. J. Bergman, “The next step for stress research in primates: To identify relationships between glucocorticoid secretion and fitness,” Horm. Behav., vol. 91, pp. 68–83, May 2017, doi: 10.1016/J.YHBEH.2017.03.003.

K. V. Fanson et al., “One size does not fit all: Monitoring faecal glucocorticoid metabolites in marsupials,” Gen. Comp. Endocrinol., vol. 244, pp. 146–156, Apr. 2017, doi: 10.1016/J.YGCEN.2015.10.011.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2022 50SEA

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.